Jussi of the Month November 2021

Don Carlo with a new boss (November–December 1950) – part 1

The season opening at the Metropolitan Opera has always been important. Like La Scala in Milan, it was normally delayed until late autumn, marking the restart of life in higher echelons of society. Nowadays both houses start performing in September, but in Jussi Björling’s days it was November. Then all fine families should fill their boxes in the Golden Horseshoe, ideal for viewing each others and not just the performance. Often the latter was a new opera production, but sometimes a revival with some particularly prominent singers would have to do. In both cases it became a kind of manifesto from the management of the theatre: look here, we are worthy of your support through attending performances and donating your money!

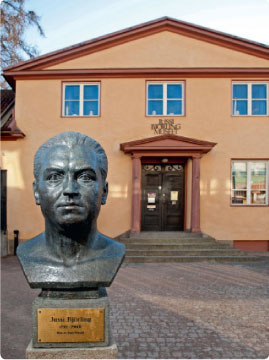

The upper part of the old Metropolitan Opera auditorium

Jussi Björling had inaugurated the Met season once before, in 1940. Then the occasion was a new production of Un ballo in Maschera. Despite the war he had returned to the US from Sweden, and the new production linked to his Swedish nationality by showing Gustav III’s Sweden even though the role characters retained their Italian names Riccardo, Renato etc. In 1949 he almost inaugurated the season; the first-night Rosenkavalier was followed by a newly staged Manon Lescaut as the second opera of the season, where Des Grieux was a new role for him which he had tested a month earlier in San Francisco.

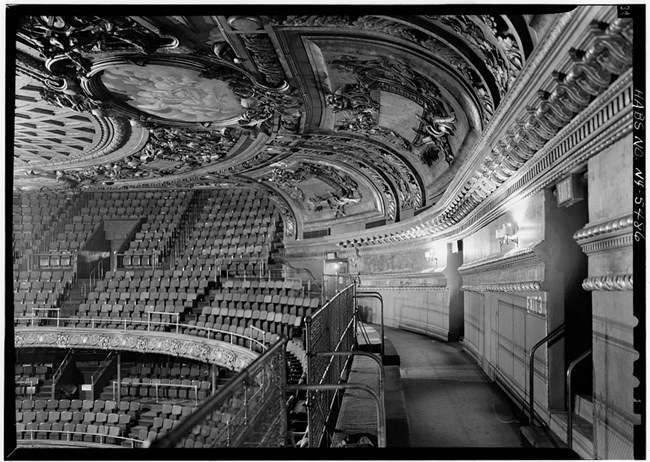

Edward Johnson

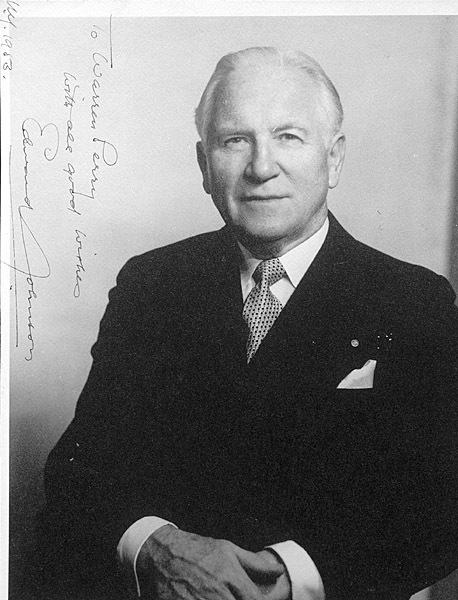

Rudolf Bing

situation: an affluent audience accustomed to a starry operatic season, a good orchestra, but primitive conditions backstage. The opera house from 1883 was dilapidated, as were the stagings and sets – and discipline. In his memoirs Bing calls the conditions scandalous. There were too few rehearsals, and repertoire and productions (sets and stage direction) had deteriorated and needed replacement.

As a music administrator in post-war Britain Rudolf Bing was used to a constant lack of resources and parsimonious productions. For his new job at the Met he took inspiration from the new trends in opera he had experienced in inter-war Germany as well as the new conditions and tastes he saw emerging among the young, post-war generation. To attract them performances would have to be fresh and well-rehearsed; there was now a new generation of artists which had not been introduced to US audiences; and media should be better explored. A few Met performances had been seen on live television, but television audiences expanded rapidly, and Bing’s first Met opening would become the first to be seen on TV.

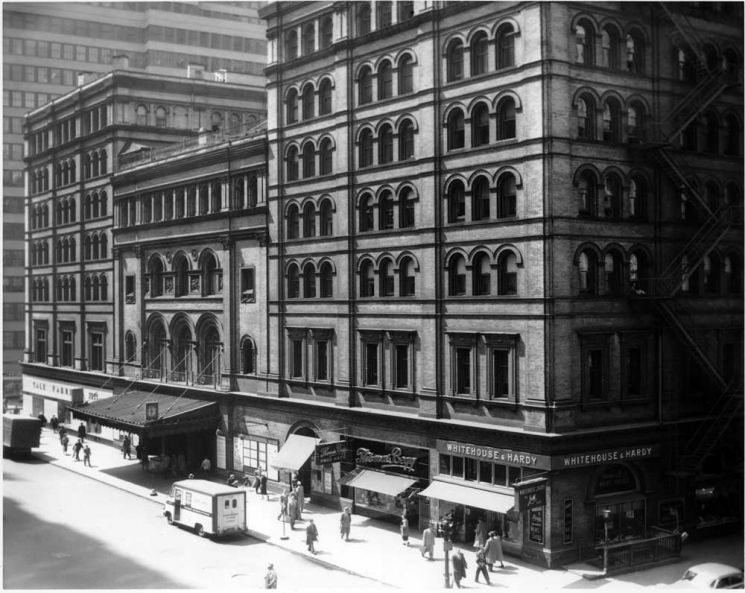

Met 1950

Bing chose Verdi’s Don Carlo which had not been performed at the Met since the 1920s and a stage director and a scenographer who had not been tested there: Margaret Webster and Rolf Gérard. The conductor Fritz Stiedry had been at the Met for a few years, but he had also first-hand experiences from Gustav Mahler’s Vienna State Opera and Berlin’s 1920s. Bing had encountered him already around 1930, and they shared a view of Verdi’s opera that they had acquired in 1920s Berlin: Don Carlo was a neglected piece of great potential. As part of the so-called Verdi renaissance, it had been introduced or reintroduced at several European stages, as in Stockholm in 1933 with Einar Beyron in the title part.

Jussi as Don Carlo 1950

Among the other main characters there were three Met debutants. Cesare Siepi (King Philip) was just 27 but already a big name in Italy. Delia Rigal (Elisabeth) and Fedora Barbieri (Eboli) had both just turned 30. Compared to her colleagues Rigal would go on to a shorter and lesser career, but at the time and for some years to come she may have been viewed as a serious challenger to Renata Tebaldi.

Fedora Barbieri, Robert Merrill, Jussi and Delia Rigal in connection with the performance of Don Carlo 6 November

Tebaldi was a little more than one year younger. She had just made her US opera debut in San Francisco, and it is easy to imagine how thrilling it must have been for operagoers with all these new names around. Rigal would remain with the Met until 1957, but by then Tebaldi had had her Met debut (in January 1955) and totally eclipsed her Argentinian colleague.

Of course, Bing had not personally discovered these young singers; they were well established in Italy where a new generation was launched to supplant singers who during the war had become old, burned-out, or politically compromised. In accordance with the old saying about new brooms Bing not only favoured new artists, he also got rid of several older ones. Jussi would soon be one of the few remaining with experience from the pre-war Met – and so able to compare Bing’s leadership with Edward Johnson’s.

Still there were of course in Don Carlo singers who had started their Met career under Johnson. But they too were young. Jerome Hines was the exceptionally young Grand Inquisitor at age 29, but he had made his debut already at 25 in a smaller part (and his opera debut in San Francisco a few weeks before his 20th birthday as Biterolf in Tannhäuser and Monterone in Rigoletto – surely a record for a bass?). Robert Merrill, 33, already had five Met seasons behind him.

It is probably unique that a major international opera house entrusts such a young cast with an opera like Don Carlo where all roles require large voices, vocal and stage maturity, and contain moments of great drama. For Jussi Björling it probably was a new experience to be the senior veteran: six years older than any of the other leading characters (who as we have seen were between 27 and 33), and without comparison the artist who was best-established with the audience.

Did he already feel fed up with the operatic career which had dominated his life for exactly twenty years? The obvious alternative was to earn money from recital tours on his own with just a pianist and sometimes wife Anna-Lisa as companions. The last few years such concerts had been the larger share of his public performances. Maybe they reminded him of his tours as a boy, and at least he was spared his new boss’s orders. Both the memoirs Anna-Lisa co-authored with Andrew Farkas and Bing’s autobiography describe conflicts focusing on Jussi’s participation in rehearsals. Bing wrote to Jussi that “It is one of the foremost objectives I have in mind, to establish real rehearsal discipline”, and “it simply cannot go on like this. Please let us avoid a major trouble…”. In his memoirs Bing says that later in the season he heard that Mr Björling had said he was “unable to afford” continue with the Met. Bing and Anna-Lisa Björling partly quote the same letters between them.

Not unexpectedly, Anna-Lisa and Bing see the situation differently. Under Edward Johnson there had been a “unique familial camaraderie”; he was a gentleman who spoke the same language as his singers, while Rudolf Bing maintained a remote distance. “Discipline may have been lax, chronic financial difficulties meant that rehearsals were few, and scenery was often carelessly erected and in poor repair, but Eddie had taken over the Met in the middle of the Great Depression, brought it back into the ‘black,’ and managed it well during the difficult war years. It was unfortunate that now, at the brink of the United States’ new prosperity, he no longer felt the requisite stamina to continue.”

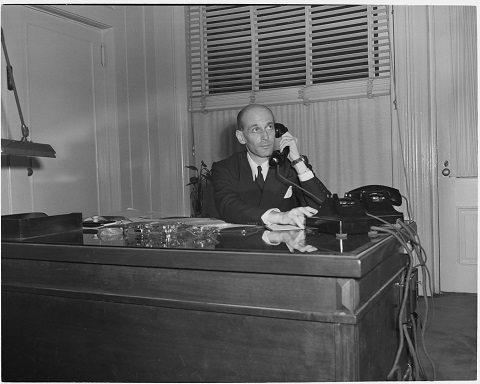

Rudolf Bing in his office at Met

According to the biography by Godor and Rodén (Mästersångaren från Västerås; Atlantis 2015; the quote below is in my translation), the Met’s other Swedish tenor Set Svanholm had a far more positive opinion of Bing. In a letter home to his wife in Sweden he told how Edward Johnson already in spring 1950, before Bing would take over, had started criticizing his successor “for publishing his opera plans while the last Johnson season is still going on! And called Bing’s plan ‘over-advertised’! It is simply unbelievable! It just shows how Johnson’s complex over his own limitations has grown him over his head, and that it now is just his constant farewell parties that can give him satisfaction, while the departing troika for whom this is not enough devote all their energy to criticize and bad-mouth Bing! Distasteful! Small! Disgraceful!” Godor and Rosén also cite letters from Sigurd Björling to Set Svanholm from December 1950. Svanholm had told Sigurd Björling about Bing’s “tough regiment” at the Met, and the colleagues agreed that some of that would not come amiss in Stockholm, where the climate was “indolent”. Six years later Svanholm would himself become general manager of the Royal Opera.

There had already been a conflict over when Jussi would arrive in New York to prepare for Don Carlo. He had promised the San Francisco Opera to learn Calàf in Turandot and appear in it during October. Negotiations between the chairmen of the two theatres’ boards were needed in order to decide in Met’s favour, so San Francisco got neither Turandot nor Jussi Björling that season. Instead he participated – as we have seen reluctantly – in rehearsals in New York, and only after Anna-Lisa had talked him into doing so did he accept going to the press conference the day before the Don Carlo first night, at eleven o’clock and smartly dressed. It is difficult to avoid the impression that Bing’s arrival for Jussi signalled the end of the old, ensemble-based mode of performing opera he had learnt in Stockholm. Rudolf Bing demanded a new, media-adapted way of working where every new production would be regarded as a reappraisal during long rehearsals of what established singers believe they already know. Was this the reason it became his last new part? He would take part in one more Met first night, 1953 in a new Faust staged by Peter Brook whom he did not appreciate. In a later interview quoted by Anna-Lisa he talks of “anachronistic flights of fancy [which] are aberrations, and disturbing; they are out of character with the opera and help to defeat opera’s purpose.”

Yet he continued to sing Carlo in the new production. After its first night on 6 November 1950 there were nine more performances before the New Year, one of them in Philadelphia. The last one of the sixteen Don Carlo performances during his career was in Los Angeles in November 1958. The year before there had been one in Chicago, but the remaining fourteen were at the Met and in the production inaugurating the 1950/51 season. Some critics found him “much too lyric”, with beautiful sound but without the detailed work on character and the sombre drama they thought the role required.

The most widely known memory of the production is of course the duet with Robert Merrill they recorded on 30 November 1950. It would remain Jussi’s only commercial recording from Don Carlo. On 3 January 1951 it was joined by four other tenor–baritone duets by Björling and Merrill which probably are even better known, particularly the one from Les pêcheurs de perles. The excerpt from Don Carlo begins with the words Io l’ho perduta! – “I have lost her”. In the four-act version of the opera used at the Met this is Carlo’s initial entry near the start of the opera. “Her” is of course Elisabeth whom he had expected to marry in a politically motivated Spanish–French wedding, but she has now had her matrimony upgraded to instead marry Carlo’s father King Philip. After he is joined by Merrill as Rodrigo Posa the excerpt continues for a bit more than ten minutes until the end of the scene.

Click here to listen to the duet "Io l’ho perduta!" with Merrill from performance November 1950

Ditto "Ma lassu ci vedremo in un mondo miglore" in act 4 with among others Delia Rigal (Elisabeth)

When the record was made, RCA Victor’s immediate use of the duet was for a not very long-playing 30 cm (12-inch) LP (LM 1128) of Don Carlo highlights that was issued already in April 1951. The title role is otherwise absent from the disc, which only contains Philip’s monologue, Eboli’s two arias and Posa’s double aria (his death-scene). On the LP Italo Tajo sings Philip, a role he never did at the Met. Blanche Thebom who sings Eboli did participate in some performances, and Merrill was the production’s regular Posa. The record company was surely in a hurry to assemble a rather haphazard selection from the opera, by artists they had under contract. The album also existed as a box of four 45-rpm discs.

Io l’ho perduta! received far greater exposure when it was combined with the other four Björling–Merrill duets. A 25 cm (ten-inch) LP was launched a year later and reached Europe on HMV in 1954. Soon its contents could be found also on 45-rpm and the dying 78-rpm format, the latter only for the backward European market. The Don Carlo duet, different from the other four, then required two sides of a 45 or 78 record.

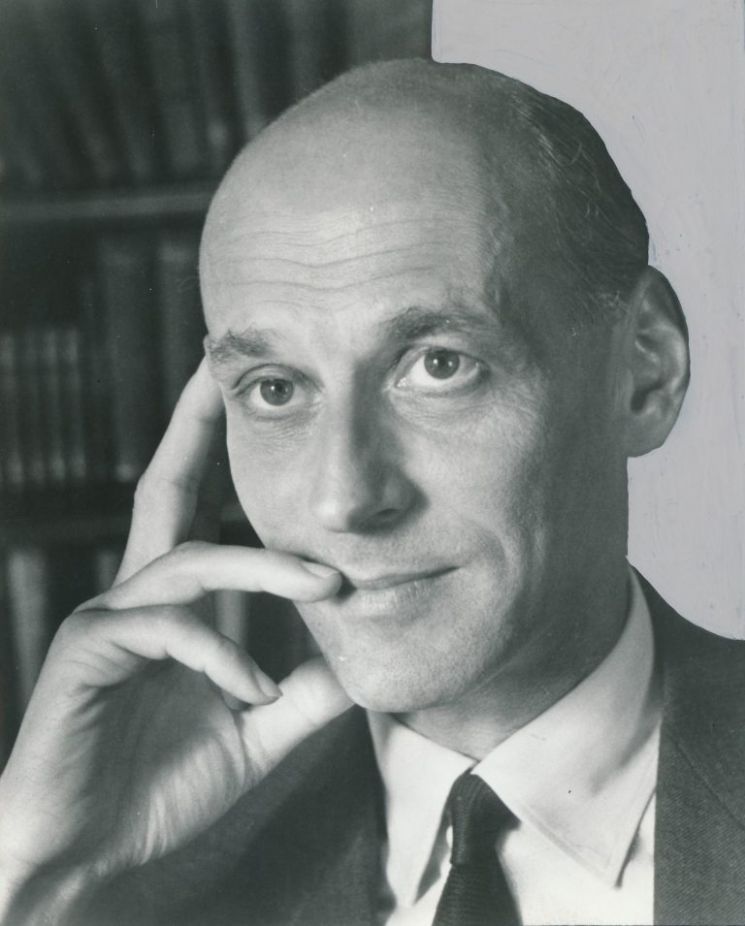

The selection features participation by a male chorus and the bass Emil Markow as A Monk. Markow (1920–2002) later performed with various local opera companies and in 1964–84 was a university professor. Through googling I found that at the time of the recording he sang in The Robert Shaw Chorale.

.jpg)

Robert Shaw

Next month we will add more about Jussi’s participation in Bing’s first night, and also prolong the story into December 1950.

Nils-Göran Olve

Click here for Jussi of the Month Summary