Jussi of the Month September 2021

Fully-fledged soloist of the Royal Opera September 1931

Early September ninety years ago the Stockholm Royal Opera presented its programme for the new season: a small book called The General Plan for the Royal Theatre’s 1931–1932 Season. This was Jussi Björling’s first year as a full-fledged member of its ensemble of vocal soloists, and therefore the first time the twenty-year-old’s name was listed among those of his new colleagues. This article is about the institution he now became part of, and where he would belong throughout the 1930s.

Recently Göran Forsling wrote in this series about Jussi Björling’s first foreign tour with the Stockholm Opera in May 1931, and earlier I have described his three debuts in the winter of 1930/31. That tour went to Helsinki where the newcomer took part in three out of the six operas given. In Stockholm he had performed the three roles of his debuts several times, and he had also done some small other parts. In total he had done 36 performances – probably more than enough for a singer who passed his twentieth birthday during the season and also was completing his formal studies.

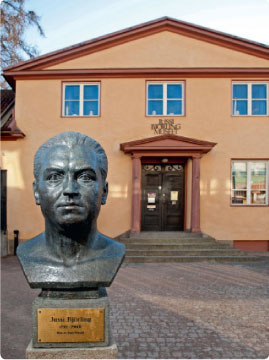

Portrait of Jussi 1931

were new to him. Three such were given already in August and September, so the new recruit had to start studying them already in the spring or directly when the ensemble convened following the summer break. Later during the season he also took part in two concerts given by the Opera: Handel’s Messiah in the Stockholm Cathedral and Beethoven’s Missa solemnis. The latter was performed at the Opera, and both were conducted by the theatre’s chorus master Tullio Voghera, who would work with Jussi on his new roles also after he had left the Opera, not least on his Italian pronunciation.

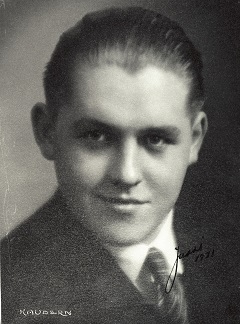

The Royal Theatre was to become the only full-time employer Jussi Björling had during his life, and if we include his year as stipendiary he belonged to it for nine years. His contract meant that he was to sing what and when he was told, often on rather short notice, and if he wanted to perform elsewhere he had to ask for a leave of absence. His relation with his boss had been established several years earlier: John Forsell – “Superintendent, Professor, Director and Chief Executive of the Royal Theatre”. Forsell had been his teacher and mentor, and we can read in the Jussi biographies by Anna-Lisa Björling, Jussi himself and his brother Gösta about episodes in their relation over the years.

John Forsell 1928

almost all his roles were big and important. In 1931 he had not yet reached that status. During the 1931/32 season there were 50 works on the Opera’s playbill, plus ballets and a few nights when the stage was given over to guest ensembles. The soloist ensemble consisted of 35 singers who between them covered almost all roles in those 50 operas. Guest singers did join them on occasion, but they were rare. So the year’s new recruit was put to work immediately.

Gustav Adolf's square with the opera 1934

The numbers are worth considering. Most of the 50 works given in 1931/32 had of course been on the playbill also in preceding seasons, with some dating from the early years of the century. They were rehearsed sparsely, because according to employment contracts everyone was supposed to remember what had been studied and performed before. There was enough work needed to prepare the season’s eight new productions. Soloists, chorus, orchestra, stagehands and the stage itself were finite resources, so when a newcomer needed to rehearse something others already knew he usually was assigned just a few hours with an assistant conductor or director in one of the smaller rooms of the building.

So in taking over roles in existing productions, like Jussi Björling did, he had not necessarily met everyone involved before the actual performance. The most important joint scenes would have received a stage rehearsal, but for the rest run-throughs with staff assistants would have to do. Everyone was, like also the stage itself, in constant demand for the productions which shifted daily.

In total there were 238 opera performances during the 1931/32 season, and then I have not counted some evenings when the Opera was just host to guests from outside. Neither are ballets or concerts included. Assuming that each opera on average required ten soloists the 35 soloists thus shared 2 380 appearances. Jussi Björling’s 67 performances is then near to the average for all soloists.

Oscar Ralf as Siegfrid

abroad. And Oscar Ralf was useful also for character parts. 18 of his 45 were in just one work: the customary “spring operetta” which this season was The Csárdás Princess. He did the romantic tenor lead’s father – a role that has a determining influence on the story, but whose demands are certainly very different from his Wagner roles!

Some new productions in which Jussi Björling took part could be performed numerous times during their first year on the playbill, for instance The Barber of Seville where he sang Count Almaviva ten times during the 1931/32 season. Without this, he might have had to take on even more roles – as older singers did who had accumulated a larger number over the years.

In addition to the operas the Royal Opera also performed ballets, which were a smaller part of its activities compared to now.

I have described this in some detail to clarify how different conditions were compared to now. In recent years the Stockholm Opera has given about a dozen operas annually, in total maybe 140 opera performances. Some works can be played twenty times or more. Few remain in the repertoire for years like they did ninety years ago, and it would be considered impossible to give all the big Wagner operas annually – especially for just one performance. This is not a suitable place to go into how it was possible ninety years ago, what is different now, and if things were better then. But to gain a perspective on Jussi Björling’s formative nine years at the Stockholm Opera it is necessary to understand the activities where he now had become a full member.

The full titles of managing director Forsell as quoted above come from the programme book for the season which I mentioned at the start of this article. I will now summarize and comment on its contents. Throughout the 1930s a similar book was published each autumn, and like I have already said this was of course the first time that a photo of a very young Jussi Björling appeared in the gallery of the theatre’s soloists. For most of the text it is the director himself who writes. The book is 50 pages including some advertisements – mostly for an affluent audience – and it cost 50 öre (half a Swedish crown), a sum which was not negligible in those days but not really expensive.

John Forsell depicted from the General Plan

who are some sort of directors. I’ve already mentioned the 35 soloists. The orchestra has 67 members, the ballet 28 and the chorus 55. “Tjänstemän” (officials) number 34, among which 6 ladies. I guess that stagehands, ushers and various craftsmen in the theatre’s workshops are not included here, but are in addition to the 229 we have been told about so far.

If we compare with the website of today’s Stockholm Royal Opera the numbers look very different. For the pandemic-struck 2020/21 season 57 singers were listed, but most are contracted per production and not permanent employees. If I have counted correctly there are 79 in the ballet (of which six are on leave of absence), 53 in the chorus and 99 in the Royal Orchestra. The growth of the ballet stems largely from the art form’s much expanded role at today’s Royal Opera. The orchestra pit has been enlarged several times, and ergonomics, work regulations and artistic ambitions together motivate that today’s orchestra is 50 % larger than it was ninety years ago. A detailed list towards the end of the 1930s shows only eight first violins against today’s eighteen, and those eight were certainly all required to play both matinees and evenings when the Opera sometimes gave five different works during three days, as it often did during Christmas and other major holidays..

But the really large changes concern the personnel that the audience does not see. According to the annual report for 2020 the number of employees (full-time equivalents) was 588 which may be double that of 1931. Many work in marketing, IT, occupational health and other functions which barely existed then, or were handled by a single official. And yet the activities are performed in the same building. In 1931 this was comparatively new: inaugurated in 1898 there were staff members who – like the “boss” himself – had been there since it was new. The time perspective is like ours back to 1988!

Well, what about the newbie Mr Björling’s tasks and colleagues? Out of the 35 soloists 20 were men, and of those eight – including Jussi – were tenors. That may seem a lot, but as we will see only one was really suited for the roles that our new promising tenor aspired to.

Birger Biguet and Olle Strandberg did character parts, the latter also small lyric parts. Henning Malm was approaching sixty and had only a few roles left. Oscar Ralf was fifty and the theatre’s Heldentenor, but not for many more years. Simon Edwardsen sang some parts that Jussi Björling would soon be doing, foremost among them Canio in Pagliacci and Florestan in Fidelio, but his strong suit was in character parts – for instance, he was Mime against Ralf’s Siegfried.

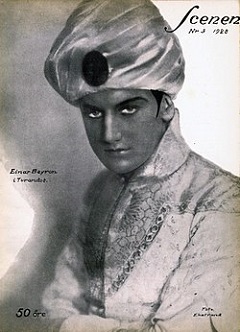

The theatre’s two lyric tenors were court singer David Stockman and a relative newcomer, Einar Beyron. Stockman was 52, had been with the Opera for a quarter-century and would remain for another decade. His Fach extended from charming lighter tenor parts, not least in French repertoire, to Lohengrin and Parsifal. He would continue to sing those to the end of his time with the Royal Theatre, and very well to judge from recordings. But he was not someone Forsell the director would invest in for the future.

Einar Beyron in Turandot 1928

was not conventionally beautiful, but expressive. He obviously found it easy to learn and was regarded as uncommonly cultured for someone who had chosen to become a singer, not least as a tenor: college educated, knew languages, looked great and could move on stage. Of course he alone could not carry the entire lyric tenor repertoire at the Opera. He abstained from Wagner’s Ring but sang almost all other tenor roles that were required. In the 1931/32 season he did 80 performances of 17 roles, all leading parts. A few years later when Jussi had “reached full speed” a normal rate was that he and Beyron sang ten times each in a month, leaving a handful of evenings for Stockman.

The young tenors did not share many roles, because each would “own” the works they had studied and knew. Beyron had those that required more acting or looks like Carmen and the annual operettas, but also Lohengrin (shared with Stockman). In Jussi’s early years Beyron alone did works that required more of a spinto voice: Aida, Don Carlo and others. There were some operas where both had different advantages, so that the audience could compare, like Bohème and Roméo et Juliette. Few operas have more than one such tenor part, so in later years they would rarely meet on stage. In the autumn of 1931 however it happened rather frequently, when Jussi Björling still singing minor parts in the operas where Beyron held the leading role.

That John Forsell favoured young artists led to a relatively high number of newly engaged singers, yet it would take long before there would be another tenor suited for the same parts as Jussi Björling. But there was a remarkable range of promising singers in other voice categories. Inez Wassner (b. 1896), Einar Larson (b. 1897), Gertrud Pålson-Wettergren (b. 1897), Irma Björck (b. 1898), Helga Görlin (b. 1900), Leon Björker (b. 1900), Brita Hertzberg (b. 1901), Brita Ewert (b. 1902), Joel Berglund (b. 1903), Astrid Ohlson (b. 1904), Elsa Ekendahl (b. 1905) and possibly one or two more were all less than 35 that autumn in 1931 – including Beyron one third of the soloists. Most would stay at the Opera for the next twenty years.

In the general plan many dates during the season are still blank. First nights, subscriptions and school performances are stated more in detail, as are a few foreign guest artists whose repertoire however has not yet been agreed. The managing director’s long text begins:

“August 3 the personnel of the Royal Theatre was summoned to resume their duties, and on the 8th, a Saturday, the first performance of the 1931/32 season took place when Wagner’s ‘Tannhäuser’ was given after having been newly studied completely…” Further down in the text, performances to be given in the latter part of September are described in the future tense, so obviously the plan is dated around 1 September.

Decor sketch for Tannhäuser by Torolf Jansson 1931

In this Tannhäuser Jussi Björling sang Walther’s part which is fairly small – especially in the Paris version which was the one performed. The larger roles were done by Hertzberg, Wassner, Beyron and Larson; Berglund was Biterolf and only the Landgrave, Åke Wallgren (b. 1873), remained from an older generation.

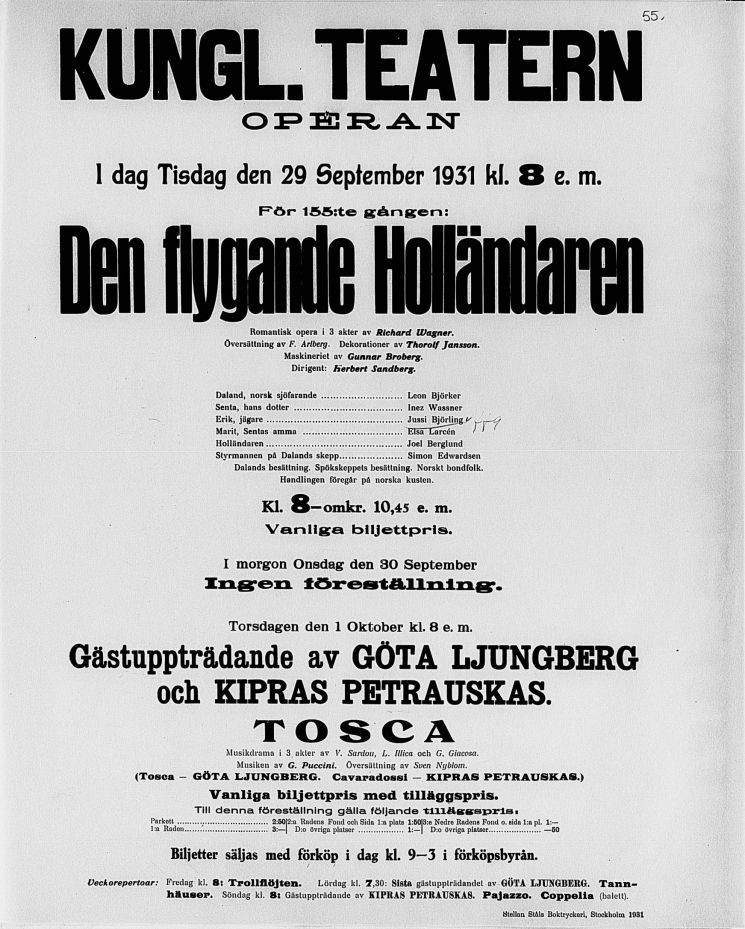

Also some new role assumptions in Aida on 22 August – Hertzberg and Pålson-Wettergren – have already happened when the general plan is printed, while a “completely restudied” Bohème on 23 September and a ”reprise” of The Flying Dutchman on 29 September are still to come. Görlin and Beyron sing in the former, while in the later we have Berglund, Wassner, Björker – and Jussi Björling as Erik!

Forsell calls August and September ”the summer season”; it seems cultural life in Stockholm does not really start until October. Only then will there be school performances or “popular performances” at reduced prices with ticket sales in the House of the People and through workplace representatives. The same applies to the subscription series for which the publication is meant to induce readers to sign up. With October we will enter “the proper autumn season”.

Young Mr Björling is mentioned when the general manager previews some future new casts, but also in this way:

“Newly engaged from this season is Jussi Björling, who after studies at the Music Conservatory and the Opera School last season absolved his three debuts.” (In the Swedish text, Forsell uses the uncommon, Latin-derived Swedish word “absolvera”, absolve!)

During August–November 1931, his first few months as an employee, Jussi’s debut roles in Saul and David and William Tell got used again, and also the Lamplighter in Manon Lescaut, Ruster in I cavalieri di Ekebù and the song-writer in Louise - small parts he had sung as a stipendiary. In addition to Tannhäuser and The Flying Dutchman, already mentioned, he performed in eight more operas which were new to him. Smaller assignments among these were Tybalt in Romeo and Juliet, once with Stockman as Romeo and once with Beyron, and “a voice in the night” in Zoraima by the Italian Montemezzi. In addition to Erik in The Flying Dutchman there was, however also one very large new role: Almaviva in The Barber of Seville which Jussi Björling did for the first time on 7 November and repeated five times only in the following four weeks. There would be twenty more performances until 1937.

So a total of ten operas during his first four months as an employee, half of them role debuts. Or if we describe it differently: young Mr Björling now had the major tenor parts in Barber of Seville, William Tell, The Flying Dutchman and Saul and David, plus six subsidiary parts ranging from important ones (Tybalt) to short and incidental (the Lamplighter). In total he performed 28 times in August–November corresponding to twice a week, to which must be added rehearsals. Different from later during the 1930s, he did not participate in any concerts during this period. 18 and 19 September – a Friday and a Saturday with no performances at the Opera and maybe no rehearsals? – he did visit HMV’s recording studio, which we gave an example from above.

Jussi and Astrid Ohlson in The Barber of Seville November 1931

singers at the Opera. It would take long before Rosina would be sung in Rossini’s original mezzo version. Figaro was another 27-year-old, the baritone Set Svanholm. I did not mention him earlier as he is missing from the 35 singers in the general plan, where he is not even mentioned. This was because the 7 November performance was his second debut, which directly established him as a force to be reckoned with. That he would become a tenor, a colleague of Jussi’s at the Met and general director of the Stockholm Royal Opera no one could guess.

Audio example Set Svanholm: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7GwjfYDFdng:

Set Svanholm sings the Factotum aria from Barber of Seville – not recorded at his debut when he was a baritone, but almost 21 years later when he long had been known as a leading Wagnerian tenor.

Astrid Ohlson had sung Rosina already in March 1930. Jussi’s nearest predecessor as Almaviva was Beyron, who now did the lead parts in nearly all the operas where Jussi still had second-plane roles: Tannhäuser, Manon Lescaut, Louise, I cavalieri di Ekebù and Zoraima. In addition to those Einar Beyron’s schedule for August–November consisted of Il trovatore, Aida, Carmen, Bohème, Madama Butterfly and The Beggar Student: twelve leading roles for a total of 31 performances. No wonder there was a need to unload some of his roles unto the new tenor wonder Björling! Management – Forsell – of course realized his potential, but also must have regarded him as an important lifeline if Beyron would get sick. Which seems to have happened very rarely. If it did Björling would not yet have been able to fill in for him as he had not yet learnt all those roles, but as all employees had to be available and on hand (unless they very occasionally had been given leave of absence) Forsell would have been able to change which work was given. Or order Björling to learn one more role, if there was a lead-time of a week or two!

Not everyone could stand John Forsell’s production rate. Einar Larson became more or less worn out but remained in the ensemble until his retirement twenty years later. Others like the soprano Greta Söderman was mobbed – if we use modern terms – by Forsell’s requirement of weight loss. She left the theatre in August 1930, a few weeks after performing the title role of Manon Lescaut when Jussi Björling gave his very first Lamplighter on the Opera’s stage.

It is more remarkable that so many of the youngsters I listed would remain important there for decades to come. Now including Set Svanholm, in the autumn of 1931 Forsell could field 14 promising singers in the age range 20 to 35 – ie 40 % of the soloist ensemble. They learned new roles each month, and if they were successful two performances per week was a desirable average – even when their roles were large and they had taken part in rehearsals during daytime.

With experienced backup from the Opera choir and the Royal Orchestra a repertoire of 40 to 50 works was evidently seen as reasonable, because this was to remain so throughout the decade. In preparation for the 1938/39 season, his last, the general manager Forsell writes: “the intensity of our work is best proved by the fact, that the Opera during the nine months of the previous season presented no less than 45 operas, sung plays and operettas, 9 ballets and performed three oratorios. I would like to know an opera institution with the same resources as those that our Opera masters, which can show a similar result, testifying to orderly and intensive work.”

With such a large repertoire it is obvious that the tasks for stage directors and conductors also were different from today’s. Among the photos of the Opera’s leading staff members there are two directors and three conductors. We may come back to those in some other article.

Nils-Göran Olve

Click here for Jussi of the Month Summary