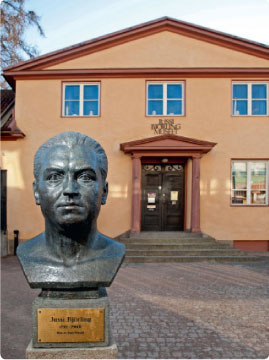

Jussi of the Month February 2021

Touring the US in February 1949

Jussi Björling celebrated his birthday on February 2, although later research has shown the correct date to be February 5. Since he had established himself as an international artist he was usually in the US that date. With exception for the war years 1942–45 and 1955 he always spent February there, except for his last four years. (In 1952 he cancelled his customary February tour at short notice, returning to Sweden on February 7 but returning in March.)

Thinking of Jussi Björling as the celebrated tenor of the Metropolitan, we may draw the conclusion that his twelve February months “over there” consisted of opera performances. From 1938 to 1959 he appeared at the Met for fifteen seasons, but his total number of performances there was fairly small – on average eight per year during those years he did sing there. The total number was 123 times, of which three concerts where he only sang a few arias. Also included is the benefit performance he and his wife Anna-Lisa took part in during Christmas 1948. There were also about ninety opera performances in Chicago, San Francisco and other American cities.

December 25, 1948 after a performance of La bohème. Edvard Johnson congratulates

According to Harald Henrysson’s documentation (to be found elsewhere on this website) three fifths of Jussi Björling’s 526 appearances in the US as an adult were concerts. They took place in 38 different states, not counting another three where he only sang as a child. The total number is 314 concerts. February seems to have been a good season for such tours, because during the eleven February months Jussi sang in the US the total number of opera performances was just eight, while he did 67 concerts. When home in Sweden, and to a lesser extent in the rest of Europe, recitals where Jussi sang his solo repertoire outnumbered his opera performances. (This refers to the 1940s and 1950s when he no longer had a fixed contract with the Stockholm Opera.)

Some concerts were with local symphony orchestras, but the overwhelming majority were with just a pianist. In the US he was almost always Frederick Schauwecker, whom Jussi’s listeners know from the four American solo recitals that have been issued on CDs. These are from New York, New Orleans and Atlanta towards the end of his life, but they seem representative also for his programmes in smaller cities during the more wide-ranging tours he made earlier in life.

Concert in the USA 1940s. Frederick Schauwecker can be seen sitting to the right of Anna-Lisa

His wife Anna-Lisa often took part, and in 1948–53 she also participated in some concerts. She had originally studied to become a professional singer, and even if it must have been nervous for her – her Swedish career had barely started before she became Mrs. Björling – it must also have been a satisfaction for her, and good for the star tenor’s image that they could appear together. On some few occasions they also performed together on radio and TV, and on the operatic stage.

Jussi and Anna-Lisa thank for the applause in Houston February 21, 1949

To get a picture of Jussi Björling’s life and activities during his best years these many concerts are important. They and his broadcasts (and in the US also TV) gave him a popular base in both Sweden and the US, far away from the opera houses. Maybe he liked them partly because he had been travelling and performed under similar conditions a thousand times already as a boy. There can have been no lack of offers of appearances in opera, but there were obvious advantages in repeating a known repertoire with just a pianist in front of an adoring audience.

Above all it was profitable financially. In the US, a country with no tax sponsorship for culture and little opera except in a few larger cities on the coasts, the pattern was that local interests would book star soloists for a few recitals during the winter season, where both local celebrities and music enthusiasts would meet up. To be a ”member of the Metropolitan opera” made it easier for an artist to request a high fee. Radio and gramophone had a similar impact. On RCA Victor’s complete opera recordings with Jussi Björling, Zinka Milanov, Leonard Warren and the other names we know so well it says ”Selected by the Metropolitan Opera”. The record company adjusted its recording and issue schedule after current castlists and the Met’s future planning, rather than Met management deciding. But for some years Met did get paid for the use of its name.

Out in the immense country artists ”of the Metropolitan Opera” of course could command higher fees, and some toured for years after they stopped appearing on the Met’s Saturday broadcast matinees or no longer made discs. Jussi’s most active touring years coincided with LP records being a new phenomenon that spread rapidly, and even small-part singers who had appeared just a few times at the Met were launched as ”of the Metropolitan Opera” for their recital tours. Maybe even Jussi Björling regarded his relatively few Met performances as a way to promote his touring. It must have been strenuous, but he could earn good money on his own conditions.

In her book Anna-Lisa Björling devotes a few pages to life on tours. 1949 was one of the years when she joined him. They had also taken part in the tours of the Metropolitan Opera, when they slept in luxury hotels and soloists were treated as royalty. Sponsors offered suppers and parties, but we know from other sources that Jussi was happiest when he could avoid polite chit-chat with strangers. But as will be obvious from my comparison of the numbers of opera performances and recitals, tours of his own were far more frequent:

”During Jussi’s concert tours everything was on a much simpler scale. Our traveling party consisted of just we two and Freddie Schauwecker. Our home was the train compartment, where we spent the entire day and where we slept every night. In the American pullman wagons of that period one could reserve ‘drawing rooms’, big compartments that were furnished with a table and sofas. It was pleasant to lounge in that living room on wheels and watch the changing landscape as the high-speed train swallowed the miles. During the night two bunk beds could be lowered together to form a wide double bed in the other part of the compartment. By tour’s end Jussi and I were so attuned to the train’s light, rhythmic movements that when we came back to our hotel in New York, we had difficulty sleeping in a bed that didn’t rock.

On the day of a recital none of us would eat anything after four o’clock. By the time the performance was over, we were starved!” (p 281 in A-L Björling and A Farkas, Jussi)

At post-concert receptions usually only coffee and cookies were served, so they then needed a real meal in a restaurant – sometimes to the surprise of other guests, who had eaten several hours earlier. Then came the best part of the day, when the party could withdraw to their rail coach:

”We’d continue to snack, play cards, discuss the concert, and talk about the people we’d met at the reception. We were fortunate that Freddie was such a pleasant travel companion, a colleague and a friend. There was never any friction between us.” (p 282)

Feeding pigeons during a tour of the USA in 1949

The programmes at such recitals followed a pattern for opera singers’ concerts which had evolved when celebrities from the music world started touring in earnest at the end of the 19th century. Agents booked appearances either in large concert halls which might hold a couple of thousand auditors, or in more intimate settings when rich sponsors requested. Before the gramophone and later radio arrived in the early 1900s audiences in many cities were rather unfamiliar with classical music. The repertoire they knew was what they themselves or friends had played in their homes, plus the few favourites they had heard on records. It was a challenge for artists to build longer programmes and yet stay within the boundaries of audiences’ taste and interest. For visitors to such recitals, comparisons with other touring singers were natural and they often focused on the impression they made on stage as much as their musical accomplishments.

Different from today’s song recitals this led to a mix of different kinds of repertoire, with each number applauded. Singers would augment audiences’ perceptions of a uniquely successful evening by adding encores, sometimes already before intermission and between the announced songs. It takes endurance to carry an entire evening alone where you sing maybe a total of fifteen numbers, in Jussi’s case sometimes even twenty, so to make a good impression you have to build an attractive mix of numbers that are sufficiently crowd-pleasing, encouraging applause for each through walking off the stage and back again. You need to “pace” the programme so that everyone is satisfied, without exhausting yourself. Often singers would start with some more classical number – a baroque aria or a Mozart group – before increasing the dynamics and the number of high notes. This is both to judge how the voice functions in a hall which will often be unknown and not tested beforehand, at least not with an audience present, and to be able to raise the intensity step-wise during the evening. Sometimes this sequence includes a few solo numbers by the pianist, allowing the singer some rest, the audience variety, and the pianist an opportunity to make an impression.

Already in the 19th century some few artists had started touring beyond the better-known “cultural metropolises” near the coasts – we may think of Jenny Lind’s highly profitable travels around the USA. This became possible with the new railroads, steamships and a growing middle class who wanted to partake of the cultural life which they could learn from the new and much more speedy media existed in larger centres. They developed an appetite to meet the fabulous Lind even though there were no recordings, nor radio. A hundred years later the appetite for Jussi Björling and his colleagues was augmented by the fact that people could hear their records and broadcasts, but as yet the diversity and quality of media did not present any serious competition for a living concert.

In Jenny Lind’s time a violinist or flautist often took part in a tour, and the main attraction was used more sparingly. Local musicians could provide a few numbers, sometimes even well-schooled local amateurs. In an era before extensive travelling was common, and with other gender roles and market conditions, there were often local women (and to a lesser extent men) who had received advanced schooling in music without making a career out of it, and ended up with a quiet family life in cities where music life was limited. They could be listed on the playbill as “a music lover”, and the guest stars only perform half a dozen numbers. Often the visitor might stay long enough to perform several times, and this certainly was a nice experience for the local high society as well as for the musicians: they made music together, travelling was less hectic, and the touring artists’ qualities were even more impressive compared to other numbers on the concert programmes. In Jussi’s days the tempo had increased through improved communications, and he would certainly not enjoyed longer contacts with local fans.

Schauwecker described Jussi Björling’s programmes in an interview. They followed a fixed pattern:

”He’d start off with a classic group of songs. Handel, Mozart, old English airs or Beethoven’s ‘Adelaide’, a particular favorite. Then came a German group: Schubert, Brahms, Wolf or Strauss. He didn’t have too big a lieder repertory, actually; just those that suited his particular talents. Then he’d do an Italian or French aria. Or maybe Lenski’s aria from Onegin; he was very fond of that. After intermission came the Scandinavian stuff: Swedish or Norwegian selections, or Sibelius songs. He often ended with Stephen Foster, or English songs that weren’t out of the top drawer but were things he loved to do and did wonders with. ‘Ah, Love but a Day,’ ‘Spirit Flower.’ Encores? He was generous with them – sometimes he’d give half a dozen or more.” (p. 30, Opera News, Feb. 26, 1972)

This is very similar to the recitals with Schauwecker we know from records, and that Jussi Björling favoured a number of favourites he knew were appreciated is also apparent from Harald Henrysson’s summaries of his repertoire. The recordings and concert-goers’ notes also show how encores – often operatic arias – were added already before the interval. These were decided spontaneously and the pianist needed to have the music available, but in reality the same small selection would have recurred throughout a tour.

The one programme kept in the Jussi Björling museum from February 1949 confirms this. On the 25 February in Charlotte City Auditorium he sang a programme which could almost be reconstructed in sound from the recordings we have of similar later Jussi recitals:

Mozart: aria from The Magic Flute (which he always sang in Swedish)

Schubert: Frühlingsglaube and Die Forelle; Strauss: Traum durch die Dämmerung and Zueignung.

Leoncavallo: Vesti la giubba from Pagliacci.

Then Schauwecker did a solo section of his own: Ravel: Pièce en forme de Habanera; Grieg: dance; Brahms: Intermezzo Op. 119:1; Lecuona: Spanish dance.

Following the intermission the printed programme showed just four more numbers: Gabrilowitch: Goodbye; Rachmaninov: Lilacs and In the Silence of the Night; Giordano: Come un bel dì di maggio from Andrea Chénier.

So in total ten songs of which three operatic arias, plus four piano solos. But five encores were added, some as usual between the regular numbers:

Puccini: E lucevan le stelle from Tosca; Sjöberg: Tonerna; Foster: I Dream of Jeanie; Verdi: La donna è mobile from Rigoletto and an unspecificed song by Tosti.

Click here to listen to I dream of Jeanie with Jussi och Schauwecker, recorded 1955

The Tosca aria probably came already before the interval, probably following Pagliacci directly before Schauwecker’s group. No one should complain during the break about getting too little of Jussi, and by then his voice had been warmed up. Both arias were certain to make a strong impression, not least because they corresponded better to the expectations people would have from a Met tenor than the Mozart aria or the four German songs did. But both are short and do not require any strenuous high notes.

After the announced programme Tonerna and Jeanie would fit well – beautiful, poignant and brief. Then – for those expecting more well-known opera and brilliance – the Rigoletto aria. And finally, maybe with gestures indicating that it was a special gift, one more song in Italian. Fifteen songs in all, plus the four piano solos.

In Houston a few days later also Anna-Lisa participated in the recital. Maybe it was more important in this larger city to exploit the charm of both appearing together. Often they would join in duets from Bohème or Roméo et Juliette towards the end of a recital.

Reading about tours by other famous singers in the US we recognized the pattern: starting with classical arias, going on to romantic “serious” composers and a few selected operatic arias, and then works from the singer’s native country towards the end. Plus of course American songs. This enables the singer to show his uniqueness, reach out to local fellow countrymen, and honour the host country.

Especially Italian singers, not least tenors, have used the same pattern into our days, when it has become customary to look down on programmes whose greatest benefit is to demonstrate the art of singing rather than to provide a coherent musical experience. The Italians would normally have learnt during their studies a number of so-called arie antiche, arrangements of baroque arias that give them possibility to exhibit their bel canto schooling. After songs by some more famous composers and a limited number of operatic arias they also reach more popular songs and encores. If like Luciano Pavarotti they prefer to avoid the German language and yet include composers from north of the Alps, Beethoven, Schubert and Liszt conveniently wrote a number of songs to Italian texts.

From January through March 1949, Jussi and Anna-Lisa were mostly on the road. On January 3 he sang in Il trovatore at the Met, his fifth performance there this winter. Then on March 29 he joined the Met party in Boston in the same opera, the first of only two performances on their spring tour where he took part. In between he appeared 23 times, among which only once in opera: in San Antonio, Texas, he and Dorothy Kirsten sang in La Bohème. San Antonio then had roughly half a million inhabitants and a symphony orchestra. In its activities a couple of opera performances were included. The organizer was San Antonio Grand Opera Festival which each spring 1945–83 gave four operas during two weekends as a festival. They were produced in the city’s Municipal Auditorium which seated an audience of 5,000, a 1920s structure later destroyed but rebuilt.

San Jacinto Auditorium February 21, 1949. Danish and Finnish national costumes

San Antonio is far down towards the Mexican border, and during February 1949 Jussi and Anna-Lisa visited seven states starting from New York and travelling down there and back. January had seen another roundtrip as far up as Chicago (Evanston), and during a week in March they travelled to San Francisco. Like I wrote before: Jussi Björling must have chosen this life in preference to working together with colleagues in opera houses, maybe adding some new role. There are similar choices for today’s singers. Solo recitals like Jussi’s have become less common, but choosing between known and new roles, glamorous solo appearances and tours based on the latest CD an artist’s choices will always reflect what they find most rewarding.

Nils-Göran Olve

Click here for Jussi of the Month Summary