Jussi of the Month December 2020

December 1935: One more night with Chaliapin

Jussi Björling rarely sang Russian repertoire. His last twenty years it consisted of just two songs by Rachmaninov (in English) and one aria each from Borodin’s Prince Igor and Tchaikovsky’s Eugen Onegin (both in Swedish). Prince Igor was a popular opera in 1930s Stockholm, and with 36 performances 1933–37 Vladimir – Jussi’s role in it – features high in a list of roles he sang numerous times. Lensky in Eugen Onegin he only sang eight times on stage. The first was in January 1933 and the final one in the month we now will survey: December 1935.

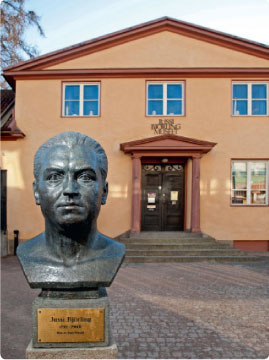

Jussi as an aged Faust, mid-30s

British but born and partly raised in Russia. Coates knew Chaliapin from Czarist Russia and conducts on some of his gramophone recordings. That both were in Stockholm at the same time makes one curious about their contacts at the time.

On Youtube you can find Chaliapin and Coates in an aria from Prince Igor, as Kontchak, one of the two roles Chaliapin sang in Stockholm.

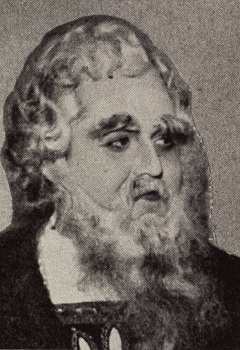

Chaliapin as Méphistophélès in Gounod’s Faust

the opera was Faust, where they would meet much closer.

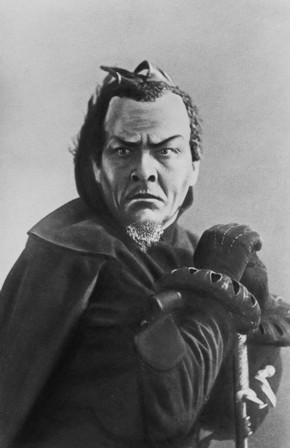

Chaliapin was 62 and Jussi barely 25 when they collaborated, but judging from recordings the Russian was still in good shape. This refers to both his voice and his epoch-making acting. Even still photos convey the different personalities he built. He was a master at makeup, and his posture and movements were to him as important as his singing. We can see some of this in a feature movie where he participated: Don Quichotte, made in 1933 and directed by G.W. Pabst. This is not any of the operas about the eponymous hero, but a “talkie” where Chaliapin only sings a few incidental songs. These were written for the movie by Jacques Ibert, after Maurice Ravel also had written a small cycle of songs called Don Quichotte à Dulcinée which however was not used. The film can be seen on YouTube. Theatre and film have evolved during the 87 years since it was made, but I find it still tells a lot about the person and artist Chaliapin. His contemporaries regarded him as much as an innovating creator of personalities on stage as a singer.

Jussi as Faust 1934

Jussi would instead meet a world-famous Méphisto who had started singing the role long before Jussi was born. Surely it was also for his sake that the theatre’s leadership reverted to the Marguérite whom Chaliapin had met when he last sang in Faust here in 1931: Brita Hertzberg. She had not sung it in the new production but many times in the old one which was in use when Chaliapin came last time. Including once with him, who was known for not really accepting directions but carry out his view of the opera – sometimes causing problems for fellow singers and the conductor. Who was Nils Grevillius, as so often.

Actually the stage bill does not mention any stage director for Chaliapin’s “extra guest appearance” at double normal prices. There must have been nervosity about how the evening would develop. The old sets may actually have been used, because in Anna-Lisa Björling’s and Andrew Farkas’s book Jussi we can read how Chaliapin at the first rehearsal dismissed the new ones, and threatened not to sing. Marguérite’s garden looked like a backyard! (Which it probably is.) Next day when the old decorations had been brought out he wondered why: ”the sets were just fine”!

All was not smooth during the evening either. Here is an excerpt from the book:

When the curtain rose, it was apparent that the great man had been out carousing the night before and was in poor voice. But such a trifle didn’t matter; Chaliapin was a frightening Prince of Darkness. When he appeared in Faust’s study, he gave such a diabolical howl that poor Brita Hertzberg, the Marguerite that night, standing nearby, nearly fainted. Chaliapin’s powerful personality dominated the stage in every scene – everyone else seemed to disappear, sometimes literally.

[…] on this particular evening Jussi was in exceptionally fine form. In the first scene of the opera, after Faust bargained his soul to regain his youth, Chaliapin moved towards Jussi and with a sweeping gesture covered him completely with the folds of his cape.

Singing at full volume, Chaliapin strode around the stage, holding Faust captive inside the cape. Poor Jussi struggled to surface now and then to sing his half of the closing duet. He couldn’t see the conductor or the prompter, and he told me afterwards that he almost suffocated. Finally, near the end of the duet, he disentangled himself and made sure that his closing high notes were heard. From that point on, the rejuvenated Faust kept a safe distance between the Devil and himself. Chaliapin gradually overcame his indisposition, his voice improved from act to act, the beyond-capacity audience was delirious, and the curtain fell to thunderous applause.

We didn’t realize that the trick with the cape was a feature of Chaliapin’s Méphisto. The Italian tenor Giacomo Lauri-Volpi gave the following description in his well-known book, Voci parallele.

“When a certain tenor at the Metropolitan complained because [Chaliapin] made him ridiculously disappear by enveloping him in his scarlet cape, Chaliapin replied: ‘My friend, I am Méphistophélès, you have sold me your dirty little soul, I have given you looks and youth; but now you are mine, you succumb to my will, it annihilates you. I can do with you as I please, understand?’”

After the opera they had dinner. In her book – sixty years later – Anna-Lisa wrote:

I’ve never met anyone with such a magnetic personality and mesmerizing presence. Over six feet tall and powerfully built (and by this time stout as well) he was a man of immense charm. In a social context he was a perfect gentleman in dress and manners. In the wake of his visit we were left feeling that a powerful force of nature and just moved on. Despite everything, we wouldn’t have missed it.

Feodor Chaliapin

The complete scene is available at Youtube with Chaliapin from Covent Garden 1928. We don’t hear any howl, though. Faust here is Joseph Hislop, with whom Jussi studied in the summer of 1934 – see Jussi of the Month, April 2019.

Helge Malmberg in Svenska Dagbladet mentions the guest’s cold which he, however, “conquered”. According to the reviewer, ordinary Méphistos tend to be men of the world – good-looking, elegant, rather nice – while Chaliapin is “part of the force who want evil: in one word, the Fiend himself in gestures and movements, makeup and musical characterization”. After a touche from the orchestra and flowers from the head of the Opera Chaliapin bade farewell with a humorous and well-formulated speech in French where he regretted that he had not been able to give his best. According to Dagens Nyheter applause and celebration took half an hour and reached its culmination when Chaliapin walked to the wings to use manual force to make Nils Grevillius share in the adulation.

Following his guest appearances in Stockholm Chaliapin was scheduled to do Faust also in Copenhagen. But according to Svenska Dagbladet he criticized his Danish colleagues two days long during rehearsals and left the theatre. The performance took place without him. He did relent and offer to come back the week after instead, but this was not accepted. According to Dagens Nyheter he thereby relinquished his fee of 12 000 Danish crowns.

For Jussi Björling, December 1935 apart from this was a normal month of work – maybe less strenuous than others, but with ten performances of various kinds still relatively diligent. In spite of having sung Messiah in the Stockholm Cathedral the night before he started the month with Bohème on December 1. Following the Faust on December 3 there was actually one week until his next performance at the Royal Opera: Eugen Onegin. It seems however that the guest conductor Albert Coates, whose guest appearances were just this performance and Le nozze di Figaro three days later, had been allowed rehearsals. To judge from the reviews, see below, these particularly concerned the orchestra, but surely Jussi must also have been working with him.

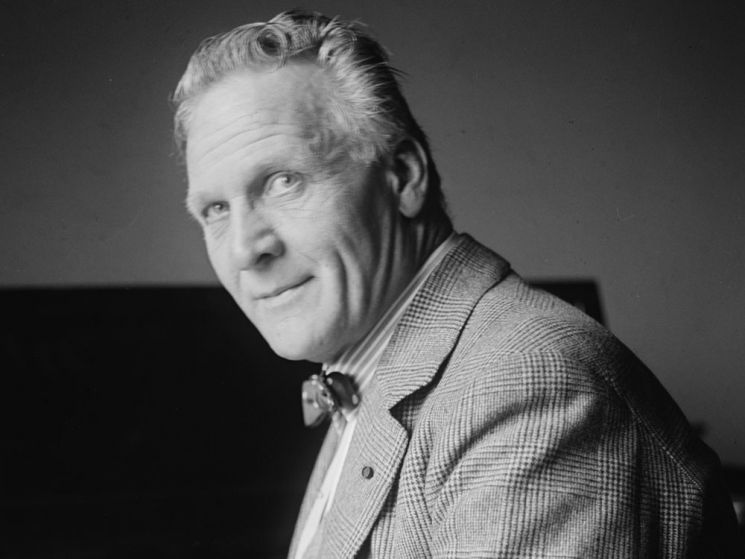

Albert Coates

At Coates’s two concerts in the Stockholm Concert Hall in March 1935 especially Tchaikovsky’s

Pathétique symphony had made a big impression. Now he had been hired for a longer period, during which he gave five different programmes 22 November–9 December. He also participated in a song recital by his wife Vera de Villiers. His two performances at the Royal Opera may have been an improvisation, as he stayed almost a month in Stockholm. This long residency may have come about because the chief conductor of the (now) Stockholm Philharmonic Václav Talich had been struck by ill health. Coates may even have hoped to take over the position, because in England his success was on the wane. In the USA during the war his prospects did not improve, and his final years he would spend in his wife´s native country South Africa – increasingly forgotten in the capitals of the music world.

For the song recital another pianist accompanied most of the numbers, but when his wife sang songs he had composed himself, her husband took to the piano. She also sang some works by him during the orchestral concerts. His presence in Stockholm during Chaliapin’s visit is interesting as they knew each other very well. Coates was born in St. Petersburg 1882 to a British family. His father was the local head of a subsidiary to a British company. After periods in England and Germany Coates was chief conductor of the Mariinsky theatre in St. Petersburg during the 1910s. When the revolution came, the Soviet government appointed him president of all Russian opera houses. But after a few years he found the situation impossible and left the country. The Stockholm press called him a Russian conductor.

Even if Chaliapin travelled extensively already in the early years of the century he and Coates must have met in Russia, and we can assume they met while in Stockholm. It is also likely that there were rehearsals for Eugen Onegin in preparation for the performance with Jussi on December 10, the day after Coates’s last performance at the Concert Hall (where he returned next year), particularly as the conductor with his Russian background knew the score well and must have wanted to impose his own ideas on it. Moses Pergament in Svenska Dagbladet devoted most of his review to praise for Coates. Einar Larson’s personification of the title role had become “considerably more mature”, while Hertzberg’s Tatiana was “a character study where the smallest detail is intentional". Jussi Björling is mentioned with no comment at all, but Curt Berg in Dagens Nyheter wrote: “Jussi Björling had his positive moments, even if they were harmed by an embonpoint (stoutness) that Lensky should not exhibit if he wants to be perceived as a tragic figure”!

In between his performances at the Opera Jussi Björling took part in a “Barbara celebration” at Par Bricole, a still operating men’s club, and in two “Lucia” concerts – a Swedish custom in the time around December 13. At Par Bricole he met the King, who was there as a guest because a new portrait of him was inaugurated. The cantata sung by Jussi was also new.

Following that he and colleagues travelled to Malmö for guest performances by the Royal Opera. On 15–17 December he sang Wilhelm Meister in Mignon. Only soloists and conductor were dispatched to Malmö, where the conductor had rehearsed a local choir and orchestra in the piece. This model was utilized during some years, also for a few smaller cities, with state support through a national organization.

Listen: the aria from Mignon (Gröna Lund 1957)

We must assume that Jussi’s private celebrating of Christmas – his first as a married man, and with Anna-Lisa pregnant in the eighth month – must have been a calm one. On December 26 he sang his final performance for the year: Die Fledermaus. Just like in Faust Brita Hertzberg was the female lead. Die Fledermaus was unusual in requiring the services of both the Stockholm Opera’s leading lyrical tenors: Einar Beyron as Eisenstein and Jussi Björling as Alfred. They normally shared the tenor roles between them.

During three days, 26–28 December, the Royal Opera gave five performances: Värmlänningarna (The Wermlanders, a popular 19th century Swedish musical play) as matinée on the 26 and 28, and in addition to Die Fledermaus evening performances also of Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg and The Csárdás Princess. Martin Öhman was the guest tenor in Meistesinger while Beyron took the lead part in The Csárdás Princess. The chorus (44 employees) probably had to be at full force in all five, while some of the orchestra (68 players) may have been excused in the lighter works. But still – what working hours!

By comparison Jussi had a lighter workload: just one Alfred during two entire weeks. But the first week of January he would sing every other day in three different operas, and some days later it would be time for his very first Canio in Pagliacci. So, he may have finished 1935 with rehearsals for this.

Nils-Göran Olve

Click here for Jussi of the Month Summary