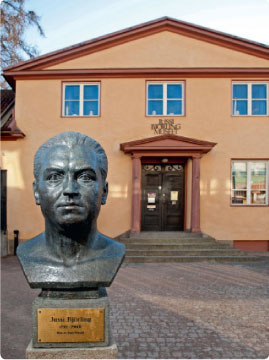

Jussi of the Month January 2020

Debut number three January 1931

Two earlier “Jussi of the Month” discussed the system of three debuts as an entry requirement to be employed by opera houses in the past. For Jussi this had importance in the autumn of 1930 when he simultaneously still was a student at the Royal Music Conservatory in Stockholm and already had been contracted as a stipendiary at “Kungliga Teatern”, then the official name of the Stockholm Opera. When he made his first debut in August that year he was just 19½. It was as Don Ottavio in Mozart’s Don Giovanni which was performed in Swedish as Don Juan. Debut number two was between Christmas and New Year’s Eve as Arnold in Rossini’s Guillaume Tell, or Wilhelm Tell. Even though we can read that he the same month was awarded the Conservatory’s jeton or medal at its finishing ceremony, something given only to its best students, he seems to have followed some of its teaching during the following months, and taken part in some student concerts. At the same time he would start his employment with the Opera in earnest. This came to last for ninth seasons: 1930/31 as a stipendiary and from summer 1931 until summer 1939 on a regular contract. In total he did fifty roles, big and small, before relinquishing his fixed employment. Of course he continued as a guest artist until his death 1960, but during this long time he added only two new roles (plus one more on records).

Click here to enlarge the image

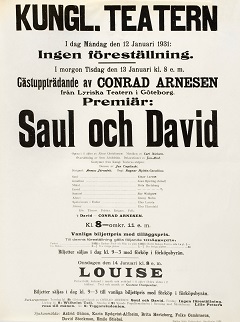

Jonathan in Carl Nielsen’s opera Saul og David and happened already on 13 January, little more than two months after debut number two. (“Og” is Danish for “and” – in Swedish it is written “och”.) During those weeks he had sung his second debut part Arnold one more time, and one evening he did a small part in Louise – one of all those minor roles which members of the theatre’s ensemble did routinely.

Forsell had differentiated Jussi’s three debuts in a clever way. First the formal and classical Mozart opera. At least those words describe how it was performed in those days. It also was a work where Forsell in person could monitor his young colleague’s moves on stage while he himself sang Don Giovanni a few metres away. As there were a few more beginners in that opera there was a reason to invest some rehearsal time, which was not always the case: other debutants might have to do with little more than an instruction session.

As debut number two a French-Italian opera, but not one of the most commonly performed. As Guillaume Tell was a new staging of an opera last seen eleven years earlier it could be relatively well rehearsed, and it attracted more attention from audience and media than if it had been a constantly performed opera like La bohème. A more common work had also given rise to immediate comparisons with other tenors of the Royal Opera; now it must have seemed natural and interesting with a new name when an old opera like Guillaume Tell returned. The renaissance for the bel canto repertoire was far in the future, and many thought of the work as old-fashioned.

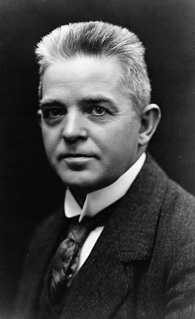

Carl Nielsen

living Nordic composer. Hugo Alfvén had not written any opera, and Stenhammar had died in 1927. Peterson-Berger and Natanael Berg were the only active Swedish composer to have had works performed by the Royal Opera; Hilding Rosenberg would be added to that short list a few years later. But Saul og David must have been perceived as an important and at the same time “safe” novelty. That its composer himself travelled to Stockholm for the occasion added extra glamour.

Some may expect Saul og David to be an edifying Old-Testament sermon with devotional choruses about the Lord’s chosen people. But Nielsen had no interest in such things, he was an extrovert country boy from Funen who at the time of writing – the turn of the century – just had had his first major successes. As in Verdi’s Otello the audience with no prior warning or overture is thrown into a situation where the next few minutes will determine the entire course of the drama. Israel’s king Saul wants to send his army against the approaching enemy, but the prophet Samuel has said that the will of the Lord is that Saul should await Samuel’s return. Saul dares to trust his own judgment in a way that we in the audience probably find rather reasonable: that the situation is acute and does not allow any delay. He starts the sacrifice which must precede the army’s departure, without attending the return and permission of the prophet. The ceremony has hardly begun before Samuel does return and proclaims that the Lord takes his hand away from Saul because of his disobedience, and that consequently a new king is needed.

Act 2 from Saul og David 14 January 1931 with Brita Hertzberg, Conrad Arnesen, Einar Larson and Jussi

When David then appears, he is at the same time a challenge and a solution for Saul’s dilemma. Here is a youth who wants to face the enemy without weapons, one that his daughter wants to marry, and whose music can calm Saul’s sick soul – but will Saul really give up his powers and be punished when his actions were driven by his concern for his people? When is it right to obstruct against a change you do not understand and find unfair? When I encounter Saul I always think of business managers whose intentions have been quashed. And I think about the entrepreneurship that characterized many in Copenhagen’s upper classes around the year 1900. Among the elegantly dressed audience for the first night of Stockholm’s Saul og David that January 1931 there must have been some who had been affected by the stock exchange crash in New York autumn 1929, little more than a year previously. Now less than one and a half year later the European economy was hesitating after “the roaring twenties”, and one year later Sweden would experience the Kreuger crash.

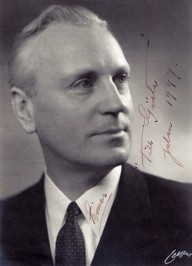

Ragnar Hyltén-Cavallius

come to the Opera some years earlier and would remain there until his death in 1941. He also had done the visual renewal of Guillaume Tell the previous month. So Saul og David was a production of its time, with the leading living Nordic opera composer coming to watch his opera, and well-established but still fresh talents forming the team to produce it.

Armas Järnefelt

Jonathan, Jussi Björling’s role, was not mentioned in my words about the plot above. He is the son of Saul who at a young age has assumed the task of arbitrator between his father’s wild temper and the internal and external forces affecting Saul’s kingdom. Jonathan immediately becomes

a close friend of David, so close that modern productions sometimes find a homoerotic side to their relation. David is the larger tenor part and for the first three performances it was taken by a Norwegian, Conrad Arnesen, who had performed it when the opera was given in Gothenburg. He was recruited because David Stockman was ill. But Stockman sang the remaining performances when the opera proved successful: it was given eight times until the early spring, and six more when it was taken up again next season.

Jussi as Jonathan 13 January 1931

Audiences came not only for the work but to experience some other favourites. Brita Hertzberg in the important soprano role of Mikal was young, 29 years, and fresh, a warm and lovable voice and person. Einar Larson, more baritone than bass in Saul’s part, was praised for an “excellent study” of the conflicted ruler. He

too belonged among the many young singers whose careers Forsell had launched at the Opera, but in his case his less than five years there had already proved too much load for his lyric voice.

Einar Larsson

lucky that his son Jonathan was played by a really young singer: Jussi Björling, still a few weeks from his 20th birthday.

All of this indicates a highly deliberate effort from Forsell to offer Stockholm audiences an attractive novelty. Hertzberg, Larson and Björling were all among his favourites, which some critical voices in the press felt he drove too harshly and expected soon to be worn out. Maybe even that attracted attention. Saul og David was a success: Svenska Dagbladet (Moses Pergament) called the first night “a tempestuous triumph”. He wrote that “For Einar Larson the role of Saul is a little too low, and maybe psychologically a line too high” but that he seemed to have benefited from a study of Chaliapin’s conception of Boris Godunov. Jussi Björling is only mentioned in passing, but another reviewer commented on his velvet-soft and beautiful voice. Even his acting was said to have improved, and writers speculated that the nervous stress was becoming less as he was gaining experience. Curt Berg in Dagens Nyheter was more reserved: ”The latter now had another debut role, whose execution was laudable, but did not add something to what he had proved earlier.” “Carl Nielsen was called up on stage, received laurels from the manager and a touche [fanfare] from the orchestra. The audience seemed singularly satisfied and their applause called back the soloists repeatedly” (Moses Pergament in Svenska Dagbladet).

,,_Stockholm_1931_low.jpg)

Conrad Arnesen, Brita Hertzberg, Carl Nielsen, Einar Larsson and John Forsell at the premiere of Saul og David 1931

Even though Jonathan is the second tenor part and lacks any real “numbers” of its own, it is important and he takes part in all four acts. Maybe this also reflects Forsell’s coaching of his apprentice. Obviously it was good to give the role of Jonathan to a singer who neither the audience nor he himself would think should have had David’s larger part instead. David is more important and puts greater demands on action and singing, but both are of a similar age and Jonathan too requires a good lyric, youthful singer. Jussi may have been an excellent Jonathan, and at the same time he will have learnt from it how to interact with brief lines with many on stage, and to react silently to the conflicts among the main characters Saul, David and Mikal.

Jussi's sound at that time:

"Höj du dig klara sol" from Romeo och Julia, recorded 29/9 1930

"Ökensången" by Sigmund Romberg, recorded 13/2 1931

With the three debuts under his belt Jussi could proceed and gradually be rewarded with more roles. During spring 1931 he alternates his three debut parts, at the end of March adding two small roles in Natanel Berg’s Engelbrekt and in April one of the “cavalieri” in Zandonai’s I cavalieri di Ekebù. He sings a total of 25 performances with the Opera that half-year, also appearing outside the opera at a few concerts and private functions. It seems likely that most of his time was spent preparing for his future as one of the theatre’s tenors on regular contract. From August 1931 there follows at a rapid pace more roles: during that autumn only, in addition to several smaller parts the strangely contrasted bouquet of Erik in The Flying Dutchman, Count Almaviva in Barber of Seville and Narraboth in Salome! But that’s another story.

Nils-Göran Olve

Click here for Jussi of the Month Summary

Tips on recordings:

Chorus from Saul och David . (On Youtube you can find some examples of the complete opera, even as video.)

From the duet Jonathan–Mikal in a recording with Niels Møller and Ruth Guldbæk 1960