Jussi of the Month September 2019

August–September 1930: Jussi’s debut at the Stockholm Opera

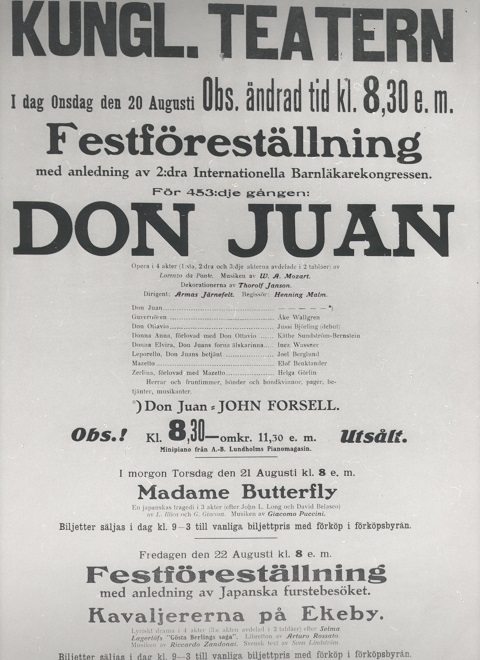

Many probably know that Jussi Björling’s first role in opera was in the tiny part of the Lamplighter in Manon Lescaut, a role which is only 18 bars long – admittedly most of them solo – in that opera’s third act. That was 21 July 1930, and the venue was of course the Stockholm Opera, or as it says on the poster “Kungl. Teatern” (an abbreviation for “Kungliga Teatern” – The Royal Theatre). The couple who were his landlords attended his performance, but it is said that the husband missed Jussi’s appearance as it lasted only about one minute.

Click on the image to get it larger

meantime, he had performed the Lamplighter once more plus another minuscule part, so the debut was his fourth performance. But before we go deeper into that we need to understand the kind of employer the Stockholm Opera of those days was, into which successful debuts could provide entry.

Click here to listen to "Höj du dig klara sol" from Romeo och Julia, recorded in September 1930

There were few opportunities for opera singers in Sweden. The title was used also by operetta singers, and there were occasional tours by temporary groups. Otherwise the Stockholm Royal Opera and the Grand Theatre in Gothenburg (actually quite a small theatre, still in existence) were the only possibilities. The latter had had ambitious opera productions during the twenties with Martin Öhman and a young soprano named Kirsten Flagstad, in addition to operetta and spoken theatre, but some years into the thirties it would focus entirely on operetta. Opera training existed only in Stockholm as a co-venture of the Royal Conservatory of Music and the Royal Opera. So if you hoped to become an opera singer you would aim for this theatre. It had a permanent ensemble, if without today’s guaranteed employment. There were at least forty soloists who could be required at short notice to take part in those operas that management decided, and if they wanted to accept invitations to perform elsewhere they needed permission – the repertoire was finally decided on a week-by-week basis, so they had to be on hand and receive their schedules at fairly short notice. This ensemble handled all parts, except for rare guest appearances by Swedes who had established themselves abroad and by foreign stars. Those then joined an existing production for a night or two, usually without more than a few hours rehearsal. Operas like Faust or Tannhäuser were performed in similar ways in most of the world’s opera houses.

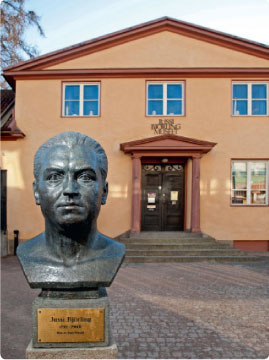

John Forsell and his students 1930. Jussi is far right

Of course, premieres or revivals of works that had long been absent required planning and rehearsals, but mostly it was expected that an opera which had been given the previous year should be possible to take up again without much preparation. The previous season 1929/30 the Royal Opera had performed 50 different operas, in addition to ballets. At this time there were few of the latter, only four that had been given a few times each. The number of performances for each opera varied widely. That season there had been eight that were new, at least to Stockholm, among them Manon Lescaut. With Carmen it had been the season’s big successes with 14–15 performances each. Many operas were given only once per year, for instance the big Wagner operas that the core audience wanted to see annually.

So becoming employed at the Opera meant to enter a production system where you learnt a number of new roles each year, but also had to be prepared to do at least twenty to thirty roles in the permanent repertoire, big and small, more or less without rehearsals. An established soloist might take part in 100 performances during the season. New productions were obviously rehearsed, but if you just succeeded an older colleague in a role rehearsing with a pianist in a small studio might be deemed sufficient. Some singers were so established that they “owned” their parts for decades, and those might deign to rehearse only if they had to meet a new singer in a leading part.

To be considered for one of the few new openings singers needed to survive the “test of fire” of actually taking part in some real performances. Often this meant to join well-established colleagues in any suitable production which formed part of the repertoire, after just a few rehearsals. The other singers might think of the newcomer as a competitor for the limited number of positions, and the audience members who were frequent visitors would compare you with predecessors in the same role. That debuts should be three in number was an old tradition. Already in 18th century France there seems to have been a right for qualified candidates to make debuts during the first month of the season as a kind of proof of their abilities, after which audience reactions and management determined if this was a singer (or dancer) who should remain. Those who failed would have to try their luck elsewhere.

In Stockholm debutants were singers who had attended the Opera College (at that time closely linked to the Royal Opera) or learnt their craft abroad, and they could rarely count on a good position or a reasonable salary straightaway. A young singer would normally become a “stipendiary” (in Swedish: stipendiat), a stage which most singers at the Stockholm Opera in those days had to pass. During one or two years and for a salary close to starvation they would be coached to enter a range of roles within the current repertoire, and in that way become useful. For the theatre such apprentices were an investment, because they required help from experienced rehearsal pianists and assistant directors – but not always on stage and with orchestra. Only when the singer had become equally valuable as her or his colleagues would normal employment be offered. This was a cheap way for the theatre to exploit young hopeful singers. For instance, one generation later Margareta Hallin was stipendiary for two seasons; when she became a “soloist” after two years she already had been a guest at the Vienna State Opera as the Queen of the Night!

This role as a stipendiary was of course something totally different from how today grants are awarded in recognition of achievements, for instance the Jussi Björling award which in recent years has been given to very established singers which in Swedish is called “stipendium”.

Successful debuts had a career value also for singers who then went elsewhere. But normally they were the needle’s eye on the path towards an intended life-long employment which would go on until the age of 53 (men) or 50 (women). This was the system of the state-run Royal Opera during most of the 1900s.

So this was the background when Jussi Björling made his first debut there on 20 August 1930. Everyone studying his career has marvelled at this: he was only 19½ years old. Sure enough he had great experience in public singing, but were his voice and acting ability really ready for a long and demanding part as Don Ottavio in Mozart’s Don Giovanni (or Don Juan as it was then called in Sweden)?

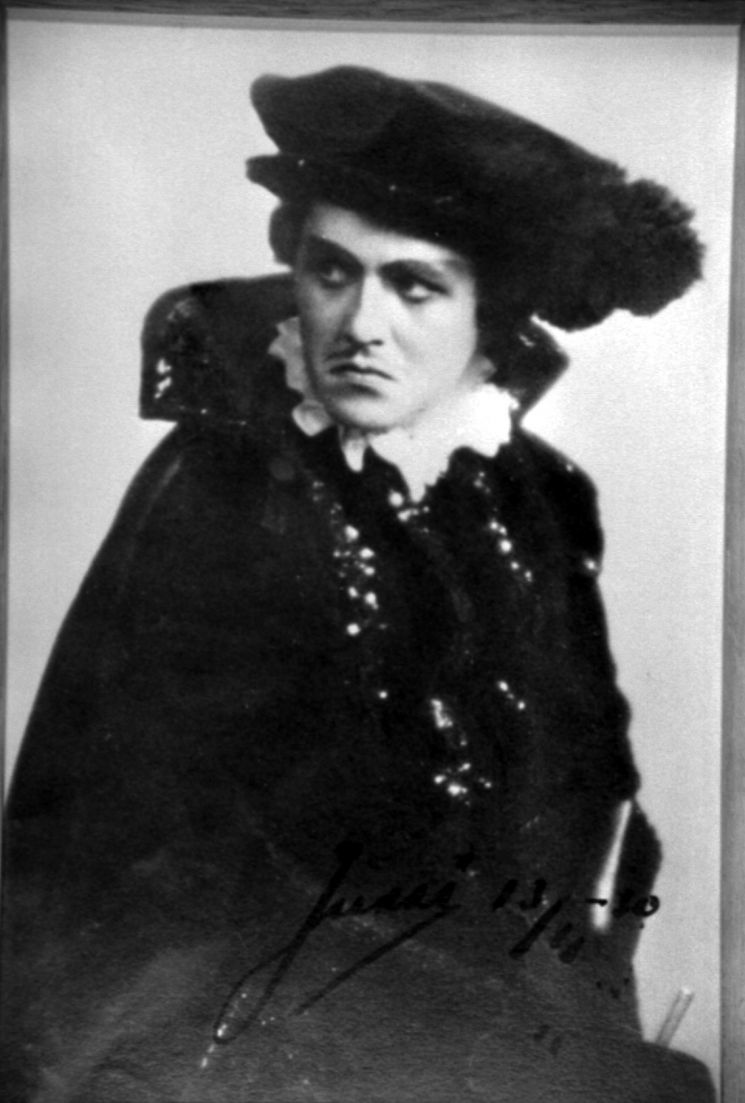

Jussi as Don Ottavio 20 August 1930

John Forsell obviously thought so – the Royal Opera’s plenipotent leader and Jussi’s teacher. He had already had his pupil expose himself in two small parts during the preceding month: twice as the Lamplighter in Manon Lescaut, and once as a poet named Nightingale in Bellman, a musical play based on melodies by that historic singer–song-writer in 18th century Sweden. The Stockholm Exhibition 1930 of Swedish Arts & Crafts and Home Industries attracted huge numbers of visitors, and probably that was the reason to start the opera season already 16 July. When Don Juan was performed the next month, it had a more specific reason: in the searchable Royal Opera archives it is called “Festive performance on the occasion of the 2nd International Congress of Pediatrics”.

In newspaper archives we discover that the performance was broadcast. Swedish Radio was in its infancy, and to allow room for an entire opera in its (of course one and only) programme may yet have been uncommon. Furthermore, this special performance commenced at 20.30, so it must have ended not long before midnight. In the tableau we learn that the weather report would have to be moved to the interval, rather than being broadcast at its customary hour.

Svenska Dagbladet on 20 August 1930

But before we ponder how this Don Juan may have been perceived by its contemporaries, I want to comment on what I wrote above about debuts.

Compared with other debutants Jussi was an exception. He still attended the Opera school and the Music Conservatory and would continue to do so during the autumn of 1930. And yet he seems to have become a “stipendiary” already before his first debut. His studies with Forsell that summer must have focused on his

upcoming debut, and it must have felt nerve-racking and challenging. That “the boss” himself did the title role that 20 August must have played a part also, for better or worse.

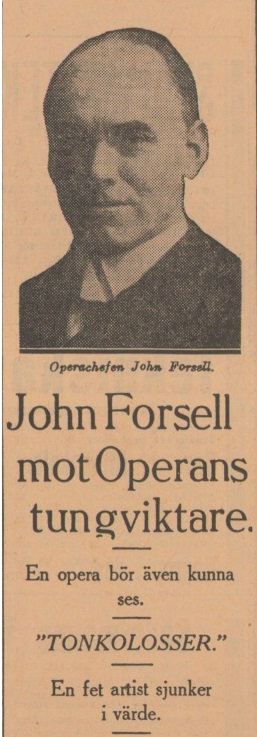

For John Forsell Don Juan was one of his most important roles. At the Stockholm Opera he had done it more than 100 times since 1898, and there would be a few more until a last one on tour with the Royal Opera in Riga 1935 – also with Jussi as Ottavio. Forsell had sung the part in the early years of the century in Copenhagen, London and Berlin, and in other German towns, but not during his solitary season at the Metropolitan 1909/10. A little more than a week after Jussi’s debut (29 August 1930) Forsell made a guest appearance in it at the Salzburg Festival, which was covered in the Swedish press. By that time his interpretation was certainly his own, but its roots could be found in his studies in Paris in the 1890s and influences from the Portuguese Francisco d’Andrade, the leading Don Giovanni of that time. Forsell’s Mozart style can be studied in a complete Le nozze di Figaro from 1937 which was issued with other Forsell recordings and exhaustive notes by Carl-Gunnar Åhlén in a Caprice album 1998 (4 CDs). It is fascinating and enlightening to consider how Jussi Björling’s style of singing was marked by two singers, both of whose ideal was formed in the final year of the 19th century: his father David and John Forsell.

John Forsell as Don Giovanni 1898

Listen to John Forsell as Don Giovanni

Forsell liked to make guest appearances in his own theatre if some special occasion merited it. By this time his roles were Don Giovanni and the Count in Nozze di Figaro, but not many years earlier he also did the Flying Dutchman and Scarpia in Tosca, roles he now had relinquished. His latest two Don Giovanni performances had been in 1928 for his 60th birthday, and in 1929 when it was court conductor Armas Järnefelt’s turn to reach the same age. Since 1910 Järnefelt was the normal conductor of the Stockholm Opera Don Juan. His final Don Juan would be on Mozart’s 175th birthday in January 1931, also a “festive performance” with Forsell, Järnefelt – and Jussi Björling.

Listen to Järnefelt's most known composition: "Berceuse"

Forsell limited his performances to such festivities and the Opera’s tours to the capitals of Sweden’s neighbours and to Gothenburg. They were grand occasions. Some of his admirers had certainly heard him already when he, as a 27-year old lieutenant (on leave) made his own three debuts at the Opera in the spring of 1896 – in the temporary opera building, as the present one was not inaugurated until 1898.

Now that he himself was the head of the Opera and sang rarely, that festive performance 20 August had a special significance, as he took the opportunity to introduce some youngsters into an opera he knew all about. The production was from 1906, and in 1930 the “normal” Don Giovanni was Carl Richter, except when the boss himself wanted to perform. The year before there had been two guest performances by the Vienna State Opera, but in Stockholm Opera scenery, with Franz Schalk conducting and well-known singers among whom Elisabeth Schumann and Richard Mayr are now the best-remembered. Schalk would also conduct Forsell’s one appearance at the Salzburg Festival in August 1930, so to some extent this was an exchange. Before Jussi’s debut Don Juan had not been given for a year, so it must have seemed a very good idea to put it on with some new casting and in preparation for Forsell’s Salzburg visit.

It was of course given in Swedish, except that Forsell is reported to have repeated Fin ch’han dal vino in Italian, as he was in the habit of doing. In a review we learn that Jussi only sang the first of Ottavio’s two arias, ”Dalla sua pace”. In Prague 1787 this was his only aria – aria number two ”Il mio tesoro” was written for the opera’s Vienna premiere the next year, as a substitute for the first aria. Mozart obviously thought of them as alternatives, but as they occur at different points in the opera most tenors nowadays take the chance to sing both. To limit oneself to “Dalla sua pace” like Jussi did at his debut can thus be seen as in keeping with Mozart’s original intentions, although it may surprise us because the only part of the opera we can hear with Jussi Björling is “Il mio tesoro” which he did not sing at his debut, and probably not in his following Stockholm performances of the role. The final sextet may also have been omitted – a Swedish Radio opera guide from 1943 claims that it “usually is not included”. Even so the singer, not yet 20, had been assigned a long and complicated role by his boss, who furthermore was able to observe how well he did at only a few metres distance.

Jussi’s predecssor as Don Ottavio since 1924 had been David Stockman, who would remain at the Opera throughout the 1930s but now left the role as Jussi took it over. Other newcomers were Käthe Bernstein-Sundström and Joel Berglund as Donna Anna and Leporello, respectively. Although it does not say so clearly on the playbill this was her third debut, following Senta the year before and Leonore in Fidelio. Apart from a repeat of Senta, this was her entire performance history at the theatre – three performances! She would remain at the opera until 1934, then sang all the big roles for dramatic soprano in Germany, and 1950 moved back to Stockholm where she became one of Berit Lindholm’s teachers. We still are some in today’s audiences who experienced Joel Berglund at the Stockholm Opera where he sang 1929-64 and in concert even later. By 1930 he had already done a number of big and small parts.

Listen to Joel Berglund as Leporello (1945)

So, the performance boasted three singers who all had sung at the Opera less than 1½ years. Such a rejuvenation must have been preceded by rehearsals, even if the production was old and their colleagues familiar with it. These must have taken place during the few weeks which had passed since the early start of the season. In that time, Joel Berglund had sung eight times and Jussi three. Joel was also a Forsell student, and he must have instructed the newcomers in detail. But had they met the orchestra and the Don Juan old-timers? The reviews don’t tell us, and the production was not announced as restudied. Jussi’s voice is described as sonorous, with a full sound and well schooled, although one reviewer though that it did not sound quite free and therefore postponed his verdict on the debutant. His movements are described as calm and natural, sensible – even though one writer advised him to avoid bow-legs.

The broadcast of course does not survive. It would be a few years until Swedish Radio had any recording equipment, and still longer before they decided to record more than brief fragments of music broadcasts. Their quality was not good enough for rebroadcasts, and when music illustrations were needed in other programmes there were commercial gramophone records. So why waste expensive lacquers and technicians’ work on something not useful? The situation was similar in the rest of the world. From 1931 some fragments of broadcast music survive; from 1932 some complete works. There are actually some recordings of broadcasts made for experimental purposes starting already in 1923, but those are exceptions.

Later during the season Jussi sang his Don Ottavio a few more times. On 25 September 1930 it was a normal performance, so the regular Don Giovanni Carl Richter returned to his role. Otherwise the cast was as on Jussi’s debut 20 August. Jussi mostly went back to his student role this autumn and performed rarely; according to Harald Henrysson’s list not at all between these two Don Giovannis. From December there was considerably more, and we will come back to that in a later “This month’s Jussi”. Jussi sang Don Ottavio for the third time in yet another “festive performance”, now for Mozart’s 175th birthday on 27 January 1931. John Forsell of course again sang Don Giovanni on this occasion, as he did for two performances in Helsinki in May 1931 – Jussi’s first foreign tour with the Royal Opera.

After these five Don Ottavios during his first operatic season 1930/31 Jussi only ever sang the role five more times: when Forsell was 65 in 1933; on tours to Copenhagen, Oslo, and Riga; and a final time in 1937 when Ezio Pinza made a guest appearance as Don Giovanni. Did Jussi get a chance to talk to the distinguished guest, who was the Metropolitan Opera’s admired Don Giovanni – also outside the stage, it was rumoured – and from 1934 also the Salzburg Festival’s? Two months later Jussi would himself travel to the US for the first time since he was a child, so he could benefit from some advice. Don Giovanni was otherwise not performed in those years, and when there finally was a new production in 1941 Jussi was an international singer who performed more grateful roles when he returned to the Stockholm Opera.

When Jussi a quarter-century after his debut sang the aria at his famous Carnegie Hall concert 24 September 1955, issued on LP not much later, he did so in Italian. He may have studied at least parts of the opera again in its original language in preparation for a Don Giovanni production in Los Angeles 1948 which was announced but never happened. If it had, we would have been able to hear more of Jussi in this part than just “Il mio tesoro”.

Listen to Jussi singing”Il mio tesoro”, Carnegie Hall 1955

But now I am getting ahead of events. After his first debut Jussi had to go through two more debuts. There will be opportunity to come back to those in another “This month’s Jussi”.

Nils-Göran Olve

Click here for Jussi of the Month Summary