Jussi of the Month April 2019

Hislop helps Jussi find his top notes

In July 1934 23-year-old Jussi Björling was already well established at the Stockholm Royal Opera, and the previous summer his international career had started with a guest appearance at Tivoli in Copenhagen. This summer there were no less than five concerts there (11-21 July), and in connection with these an outdoor concert in Malmö’s "People’s Park" some days earlier. Many new roles at the Royal Opera in Stockholm were waiting. Among those we associate with the “grown-up” Jussi he had so far done the main parts in Rigoletto, Romeo and Julia and Tosca, and one solitary performance of Un ballo in maschera. In addition he had done a large number of parts he would later relinquish, like Alfredo in La traviata or Vladimir in Prince Igor – in fact one of the roles he sang the greatest number of times. Waiting for him now were Faust, Bohème, Il tabarro and La fanciulla del West, all of which he sang for the first time in the autumn of 1934.

Helga Görlin and Jussi from Faust 25 August 1934

Even for a gifted youngster like Jussi it is natural that the voice is not fully developed at such a young age, and evidently the highest notes did not yet come with the ease they would do later. We can read how the voice was secure only up to B flat, one tone below “high C”. On recordings of ”La donna è mobile” and ”Di quella pira” (in Swedish translations) from the winter 1933/34 Jussi prudently sings in lower keys than the score indicates, so that these arias culminate on precisely a B flat rather than B viz. C. It is not clear how he did on stage.

Click here to listen to ”La donna è mobile” from 1933 (in Swedish)

Click here to listen to ”Di quella pira” from 1934 (in Swedish)

Although he remained faithful to his father David’s method of singing Jussi Björling at this time was much influenced by “the boss”, the authoritarian and admired John Forsell under whom he studied for several years. But the baritone Forsell seems to have been unable to find the tenor’s high C. Several witnesses describe how it was Forsell’s son Björn who suggested that Jussi should consult a successful tenor, namely Joseph Hislop. Björn Forsell was among those telling this much later, as did Jussi himself.

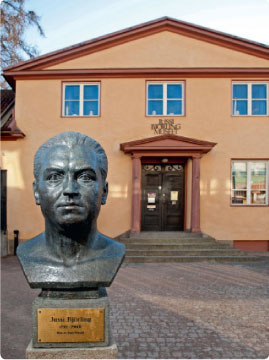

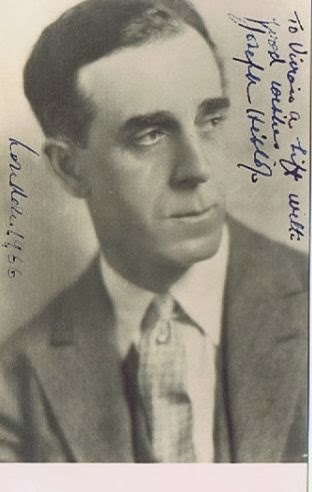

Joseph Hislop

but the book Joseph Hislop by Michael Turnbull (Scolar Press, 1992) gives the impression that he requested high fees and therefore mostly came to sing on concert tours. This probably had to do with his age. He was approaching 40 when his career took off – not quite the young promising tenor audiences at La Scala in 1923 and Teatro Colón 1925 believed. Managements wanted to pay him as a newcomer, while Hislop had higher thoughts about his worth. In his native UK he was indeed perceived as the leading British tenor, made recordings and appeared at Covent Garden, but operatic activities in the UK were limited and performances there fewer than Hislop would have deserved.

In Stockholm he appeared as a guest until 1937, and in all there were more than 300 performances within a space of 23 years. The one which has the greatest interest for Jussi Björling devotees was Puccini’s Manon Lescaut which had its delayed Swedish premiere in November 1929 with Joseph Hislop as Des Grieux. A little more than half a year later Jussi appeared in the same production as the Lamp-Lighter, a small part which was his very first at the Opera. By then Hislop had travelled on and Einar Beyron taken over as Des Grieux, but as a student Björling surely must have seen the Puccini novelty some months earlier and heard Hislop. In the early 1930s Jussi may then have experienced him as a guest soloist in Bohème and Tosca, among other roles. We can guess Jussi’s respect and some influence from the international artist Hislop, who this year 1934 was 50.

Click here to listen to Hislop from 1929 from Mademoiselle Rococo by Erkki Melartin

When Hislop’s career in those years started to decline he spent more time in Sweden, and some years later became a professor at the Music Academy College in Stockholm. He and his Swedish wife divorced in 1940 after several years of marital problems but he remained there until 1946, maybe because of the war. Sweden had been his permanent residence for 39 years, he had become a Swedish citizen and had children and friends there. After the war, at age 62, he accepted an offer of a similar teaching position in London. He would remain an appreciated professor of singing there into his eighties. He died in 1977. One of his final public appearances was in Swedish television’s This is your life, where he was invited to a programme dealing with Sven-Olof Sandberg, a Swedish popular singer whose mild baritone Hislop through stringent discipline in the space of a few years managed to expand, until he could make his debut at the Opera and sing several roles there.

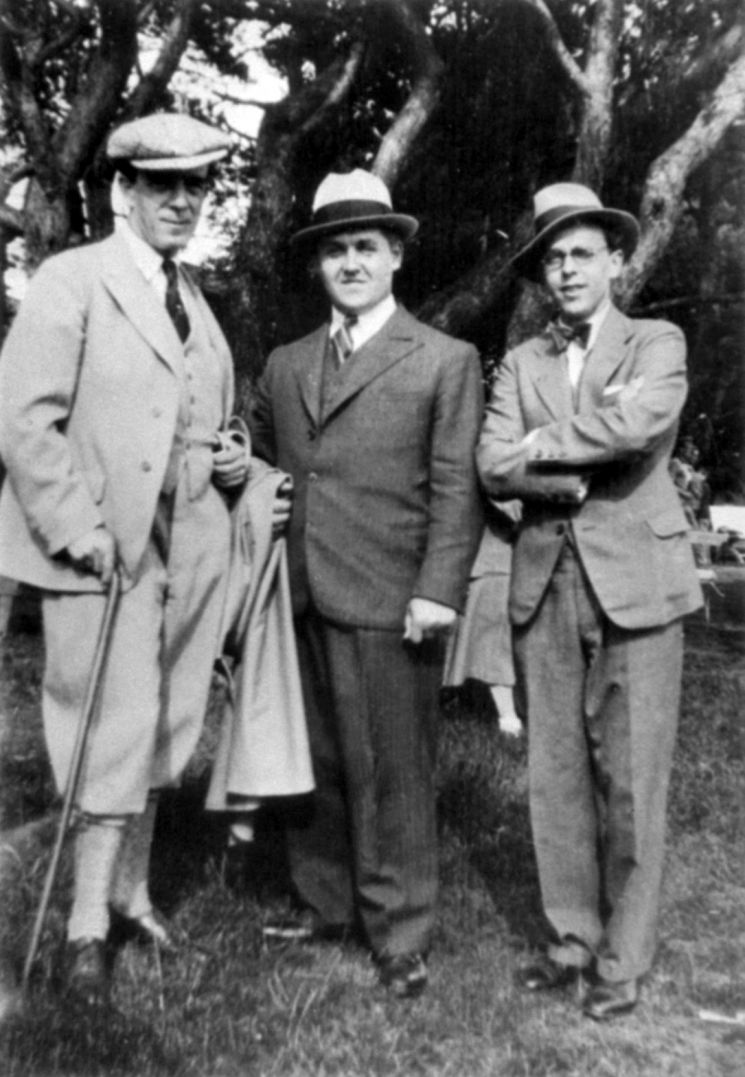

But now it was the winter of 1933/34 and I will quote those parts of Turnbull’s book that deal with Jussi Björling. The author relates how Hislop’s son described his father’s technique for singing: relax, don’t squeeze, just let the air flow. It is reminiscent of David Björling’s advice. Hislop and Jussi first met in Stockholm during the winter of 1933/34, followed by an intense week next summer at Hislop’s country house near Gothenburg. This is from p.181 of Turnbull’s book:

”Joseph demonstrated how to do it. Björling tried to sing a high C. Joseph went mad. ‘Just imitate me.’ ‘I can’t understand how you do it,’ complained Björling. ‘Just imitate me,’ said Joseph producing an effortless high C. To his great relief, Jussi was soon able to sing even a high D. Joseph was delighted and invited Björling to stay with him at Brottkärr the following summer. To teach Jussi was ‘like sprinkling water on a piece of blotting paper’: everything was absorbed at once. Always very concerned to perfect his art he learnt as much from a single lesson as a mediocre singer from six months of instruction."

Along with Jussi came another pupil, Bernt Anderberg. Both had been instructed to practise some Italian vocal exercises and were sent to a small wooden house in the garden at Brottkärr to do so. After an hour or so Joseph returned to hear the result. Jussi sat deeply engrossed in a crime thriller while his companion was still exercising religiously. Jussi, however, could repeat the exercises note for note. He had learnt them just by listening to the other student!

Joseph Hislop, Jussi and Bernt Anderberg at Brottkärr 1934

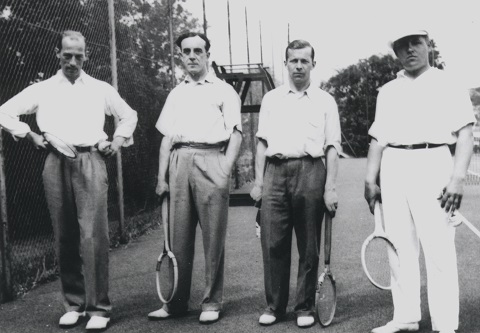

Joseph Hislop and Jussi with two unknown

The young tenor would be up with the lark (on one memorable occasion at three in the morning), his voice warm and shining as he sang standing on a huge rock in the garden looking out to the sea. ‘Look at the beast’, Joseph would mutter, ‘I have to work very hard to keep my voice in shape while he, with no practice, sings like a god.’”

Brottkärr is on the mainland south of Gothenburg and through his Swedish family Joseph Hislop had his summer home there. It is peculiar to note how it played a similar part in his career as Jussi’s summer island would do later: in the 1910s Hislop studied his new roles by inviting Tullio Voghera for some weeks, in the same way as Voghera twenty years later would be a guest of the Björling family at Siarö. Voghera was a former colleague of Toscanini and Caruso who had ended up in Sweden as an employee of the Stockholm Royal Opera, and knew everything about the Italian tradition.

Jussi and Voghera at Siarö 1940

Hislop’s contact with Jussi continued till the end of his life. Turnbull claims that Jussi could call from a telephone booth, as “How is that?” and take a high C.

It is of course difficult to know how much of Jussi’s tenor development would have happened anyway, but comparing the recordings from March 1934 and March 1935 one impression is that the voice gains core and squillo at the top. The early recordings do not offer any high Cs, and those from the period before that Brottkärr week – especially those from autumn 1933 – are largely the famous popular numbers sung by “Erik Odde”, in which Jussi emulated the style of that period’s pop singers, so forceful high notes were hardly called for.

Listening to Hislop’s excellent opera recordings, in particular the series of recordings made in Swedish following the Manon Lescaut first night 1929, it is easy to imagine him as a paragon for his 27 years younger colleague. Maybe even more than the many Swedish tenors Jussi could hear: the somewhat older colleague Beyron, the veteran David Stockman, guest Carl Martin Öhman and others. In his book The Björling Sound Stephen Hastings finds similarities with Enrico Caruso’s recordings in Jussi’s own beginning already in the early 1930s, but Hislop also had Caruso as his model – he had heard and met him in London in 1914. We can imagine how those summer nights at Brottkärr were devoted to idol worship.

Click here to listen to Hislop singing "Salut, Demeure" from Faust by Gounod 1929

Nils-Göran Olve

Click here for Jussi of the Month Summary