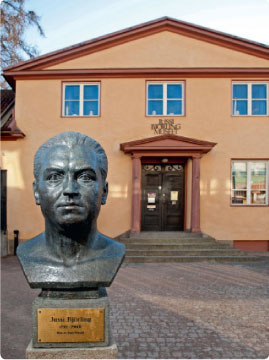

Jussi of the Month December 2014

Un ballo in maschera at the Met in December 1940

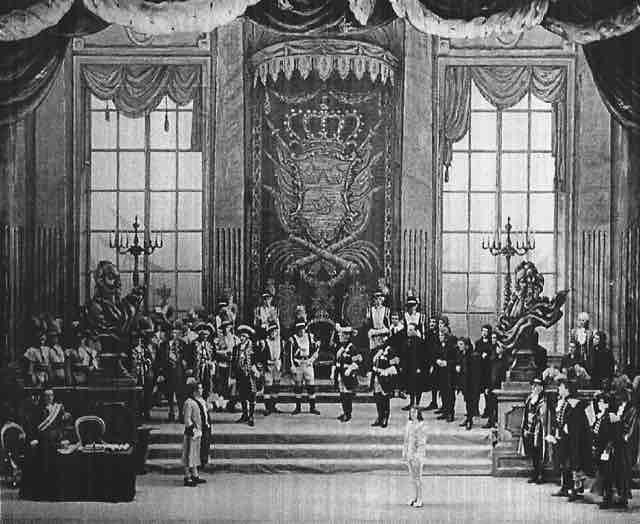

For the opening night on 2 December 1940 Metropolitan director Edward Johnson chose Verdi’s Un ballo in maschera with Jussi as Riccardo.

In the picture above can be seen (from the left): Alexander Svéd (Renato), Zinka Milanov (Amelia), Herbert Graf (stage director), Edward Johnson (Director of the Metropolitan Opera), Stella Andreva (Oscar), Jussi Björling (Riccardo “King of Sweden”) and Norman Cordon (Samuel). Kerstin Thorborg is missing in the picture. Edward Johnson had opted for the production to be as lavish and true to the period as possible, regardless of expense.

Jussi to the USA in spite of the War

In spite of the outbreak of the Second World War on 1 September 1939 Jussi made two long tours through the USA, before the nation was drawn into the war in 1941. He appeared in concerts, sang opera and made gramophone recordings. On the first of the tours he appeared between 20 November 1939 and 1 March 1940, on the second – before the war put an end to the activities – between 18 October 1940 and 27 February 1941.

When Jussi went to America in those days he usually travelled by the big transatlantic liners, a voyage that took nine days.

Boeing 314 Yankee Clipper

When the trip in the autumn of 1940 was planned the danger for mines meant that the trip by water was out of question. Instead he travelled by train through war-torn Europe and then by air to the USA on board a Boeing 314 Yankee Clipper, the biggest airplane of the day.

The journey from Lisbon via the Azores and the Bermuda to New York took 26 hours. This was the first time that his wife Anna-Lisa didn’t go with him to America but his accompanist Harry Ebert went as usual.

The tour started with a performance of La bohème at the San Francisco Opera on 18 October, followed by Un ballo in maschera on 23 October. On 4 November Jussi made a tour with the San Francisco company to Los Angeles – again with Un ballo in maschera.

The greatest event during this US-tour was for Jussi on 23 November when he sang in Verdi’s Requiem at Carnegie Hall in New York under Arturo Toscanini. Just over a week later, on 2 December, the Metropolitan Opera opened the season with Un ballo in maschera with Jussi as Riccardo.

Jussi as Riccardo

Jussi sang the role as Riccardo 38 times in toto, the first time in April 1934 in Stockholm and the last time at Chicago Lyric Opera in November 1957 under Georg Solti. Riccardo was one of his most successful roles. Jussi was only 23 when he first sang the role which is remarkably early. Caruso was 26 and Pavarotti 36 when they first sang the role.

At the Metropolitan Jussi first sang it in a production where the story was located to the court of Gustavus III, as Verdi had intended, in spite of the role names and the text from the censored version, where Riccardo is governor of Boston, was retained.

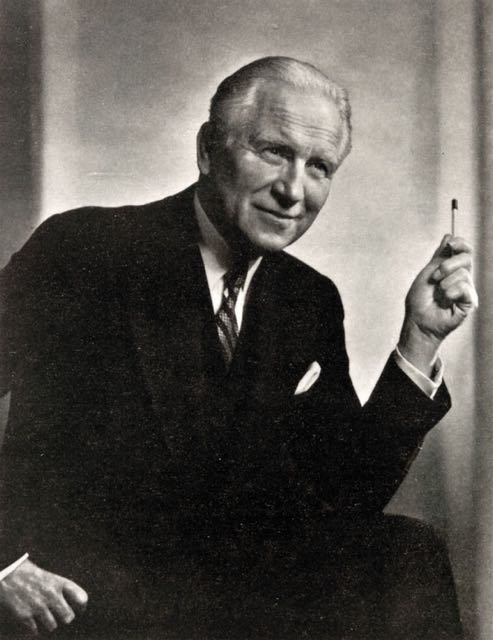

Met’s Legendary Director Edward Johnson

Thanks to the positive reviews that Jussi had had from his concert tour in America in the autumn of 1937, Met’s legendary Director Edward Johnson engaged him for the next season. On 24 November 1938 Jussi reached the goal of his dreams and made his debut at the Metropolitan.

Canadian Edward Johnson (1879 – 1959) was head of the Metropolitan Opera for 15 years 1935 – 1950, and was succeeded by Rudolf Bing. Jussi had a good and close relation with Johnson who chose to open the Met season on 2 December 1940 with Un ballo in maschera with Jussi as Riccardo.

Success and Cheers for Jussi in Un ballo in maschera

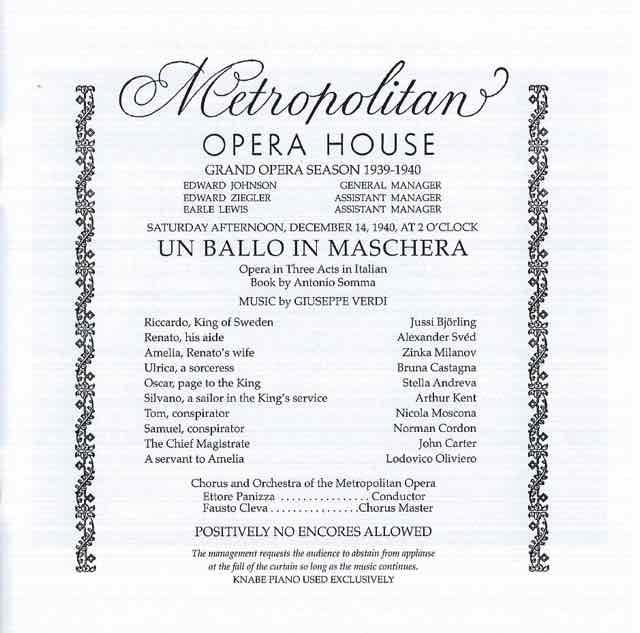

Click the programme and it will enlarge.

Jussi in the role as Riccardo/Gustavus III at the Metropolitan in 1940.

The other roles were a multinational combination. From the left Zinka Milanov from Croatia, Alexander Svéd from Hungary, Kerstin Thorborg from Sweden and Stella Andreva from England.

The opera had not been performed at the Met since 1916 when the Italian tenor Giovanni Martinelli sang Riccardo. Now, in 1940, the story was transported from Boston to Stockholm, as Verdi and his librettist originally had intended.

Met had built a copy of the National Hall of the Royal Castle in Stockholm with the national coat of arms at the back of the stage and they had procured statues of Charles XII and Gustavus II Adolphus and made genuinely Swedish 18th century uniforms for the soldiers. Jussi himself wore silk-breeches and white-powdered wig. The production was utterly lavish.

Record Proceeds for the Met

Before a record audience of 4,400 people the performance was a great success and the audience cheered. The house was sold out in spite of the tickets costing 100$ per two persons and the performance yielded 16,943$ and was the most lucrative opening night in the history of the Met, also when it comes to the fees of the artists. Jussi received 650$, Kerstin Thorborg 450$ and Alexander Svéd 400$ per performance. In 1940 a middle-sized car cost around 700$ in the US.

Great Swedish Triumph According to the Newspapers

According to the Swedish newspapers the opening of the season was a great Swedish evening, a triumph that will be long remembered. Jussi Björling and Kerstin Thorborg defended the Swedish colours brilliantly. The headlines read Jussi Björling in New York Great Success, Thunderous Applause for Jussi and Kerstin in New York, Jussi Hailed for Style and Voice, Swedish Triumph at the Metropolitan.

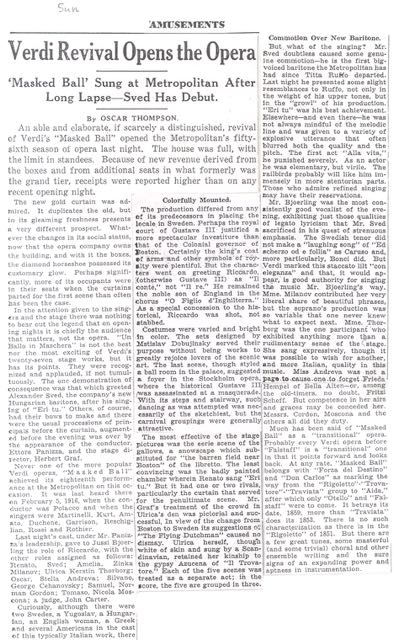

Among the American papers The New York Herald Tribune characterises Jussi’s voice as smooth and handsomely schooled. The New York Times wrote the best achievement of the evening was Jussi Björling’s, whose style and performance was artistic throughout. He was at his best in the lyrical arias. The New York Post stated that Björling sang brilliantly and Kerstin Thorborg beautifully and expressively. The New York Sun declares Björling as the more consistently good vocalist of the evening.

Björling’s mighty and clear tones put the full audience – 4,400 visitors – in veritable rapture and aroused thunderous and prolonged applause.

The production was utterly lavish and the audience cheered continuously at Björling. The success in the audience was evident and also after the performance he was met with ovations.

At large the critics of the American papers were satisfied but there were exceptions. The New York Herald Tribune pointed out that the story is incomprehensible and the roles were wrongly cast, possibly Björling excepted. He was the most elegantly costumed of the cast; and he interpreted his role with dignity and some style, if not with passion.

The New York Times finds the story silly enough in the original without having to rewrite it and name Horn and Anckarström as Sam and Tom.

Though the New York press were not wholly satisfied with the story they agreed that Jussi was the foremost singer of the performance without exception. The audience on the other hand were wholly enthusiastic. The curtain went up numerous times and Jussi was met with ovations.

Clipping from The Sun

Click the review and it will enlarge.

Mishap in Final Scene of Un ballo in maschera

A mishap occurred in Philadelphia on 17 December 1940 during a tour with the Met production of Un ballo in maschera. Jussi himself told this in a radio interview on Swedish Radio 1959. The mishap occurred when Riccardo (Gustavus III) was to be murdered in the final scene.

Met’s director Edward Johnson had given orders that the killing shot was not to be fired on stage. In the previous production some of the singers had been injured from powder-stain. This time the shot was to be fired in the wings. But everybody, including baritone Alexander Svéd as Anckarström, had to wait in vain. No shot was heard. Finally Svéd was desperate, grabbed his sword – Gustavus III had to die of course! Just when he was about to plunge the sword into the chest of the somewhat surprised Jussi, the shot went off …

Since the opera was new to the audience there was no doubt that the murder weapon was a sword and not a pistol and the shot was understood as some noise from the stage. No one in the audience seemed to bother about the little mishap.

Herbert Graf’s new production of Un ballo in maschera at the Metropolitan Opera was played with Jussi twice during December and once again on 8 January 1941. Apart from that there was a performance on 17 December 1940 in Philadelphia on tour with the Metropolitan Opera.

Giuseppe Verdi

Un ballo in maschera: "the Opera that Was Named and Rewritten Three Times”

The Masked Ball (original Italian title Un ballo in maschera) is an opera in three acts by Giuseppe Verdi to a text by Antonio Somma after Eugène Scribe’s Gustave III ou Le bal masque. Premiered in Rome in 1859 and in Stockholm 1927 (En maskeradbal).

Few operatic works have had so many problems with the censorship of its day as Un ballo in maschera. The murder of a king was regarded as an unsuitable subject for an opera and Verdi was forced to rewrite it several times. But considering the intense power struggle that was the background of the real attack on Gustavus III, which the libretto is based on, there is unexpectedly little political material in the opera. Most of it is about passion, jealousy and the conflict between emotions and duty.

Un Ballo in Maschera Is Based on an Episode in Swedish History

Un ballo in maschera is based on an episode in Swedish history. The historical picture above shows the mask that the real assassin Anckarström was carrying at the masked ball, and the pistols and knife he was carrying. We can also see the tacks and the bullets the pistols were charged with. Thye murder of Gustavus III took place on 16 March 1792 when Captain Johan Jacob Anckarström shot the King of Sweden Gustavus III at a masked ball in the opera house in Stockholm. In the newspapers one could read:

Last Friday the 16th March 1792 at ¾ before 12 o’clock when His Majesty had just arrived at the masked ball in the Royal Opera House, an unidentified mask had turned up in the crowd of masks that had gathered behind the king, and there fired a pistol, the shot of which hit a bit above the hip, not far from the spine.

Gustavus III didn’t die until 13 days later, on 29 March 1792.

Gustav III 1746-1792

The picture shows the costume that Gustavus III was wearing at the masked ball, exposed in the room at the Royal Opera, named the little cabinet, where the King was brought after the attack. This room is today recreated in the present opera house. The costume is today exposed at the Royal Armoury within the Royal Castle.

Scribe in the 1830s was already rather free in his treatment of historical facts. With the Italian adaptation contours were further blurred, and Verdi’s first version was not to be the final one.

The murder of a king on the stage was a delicate subject at the time after the attack on Napoleon III, so the story had to be transported outside Europe and the characters had to be changed. For that reason the premiere version takes place in Boston during the English Colonial Empire in the 17th century with a governor as the central character, Riccardo. This version is even today the usual one on international stages, but of late there has inn several places been a return to the setting and characters of the original version.

Passion on the Edge of the Precipice

At the Royal Castle in Stockholm an attack on Gustavus, the King, is being planned but he waves aside the warnings of a conspiracy. The king is possessed by desperate and destructive passion for Amelia, the wife of his counsellor and friend Anckarström. With the threat of death hanging over him he searches out his beloved. In a cold, dark, wintry Sweden a masquerade takes place, filled with deceit, political machination and longing for something quite different.

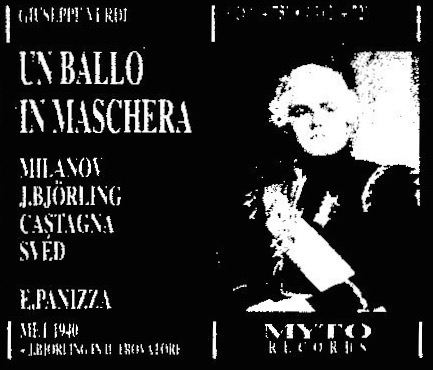

The Recording of Un ballo in Maschera on 14 December 1940

Twelve days after the premiere at a Saturday matinée at 4 p.m. on 14 December 1940 the performance was broadcast live on American radio and was recorded. The cast was the same as at the premiere on 2 December with the exception of Kerstin Thorborg who was indisposed and was replaced by the Italian mezzo-soprano Bruna Castagna as Ulrica.

But it was more than 20 years before the recording was issued on records. It was first issued on LP in 1962 but not by a record company. Instead it was Jussi’s friend Edward J. Smith who issued quite a lot of “private records, not for sale” on the label The Golden Age of Opera. Ballo had the number EJS 230. It was possible to subscribe to these records but they were not normally available on the market. In well-stocked shops one could find the Canadian label Rococo, which in due time issued 8 recordings with Jussi. Ballo was issued in 1973. The first “official” issue was Metropolitan’s own in 1981.

Myto 2 MCD 903.17 was the first record company to issue the recording on CD, and after that issue in 1990 around a dozen companies have issued Ballo from 1940.

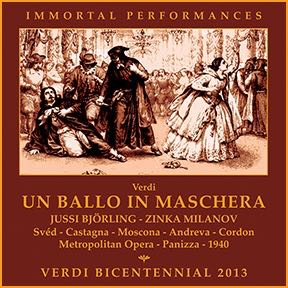

We recommend the Canadian Immortal Performances IPCD 1033-2 (double-CD) which was issued in September 2013. It can be ordered from the Jussi Björling Museum. Member price 270 SEK plus postage.

The recording from Met 1940 of Un ballo in maschera was not Jussi’s first recording of music from the opera. The very first was from the soundtrack of the movie Fram för framgång three years before that in 1937. There Jussi sang Di tu se fedele. It is available on Bluebell ABCD 092 Fram för framgång.

Jussi Made Two Complete Recordings of Un ballo in Maschera:

14 December 1940, New York Metropolitan Opera. Issued by Immortal Performances IPCD 1033-2, in connection with the Verdi year 2013.

22 April 1950, New Orleans, Municipal Auditorium, issued by VAI Audio and Cantus.

Listen to tracks from Un ballo in maschera, recorded on 14 December 1940:

1) Di tu se fedele from Act I Sc 2 Riccardo - Jussi Björling 4:02 min

2) Forse la soglia attinse from Act III Sc 2 Riccardo – Jussi Björling 3:59 min