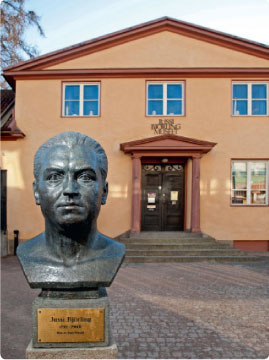

Jussi of the Month May 2022

Nils Grevillus, Jussi’s favourite Swedish conductor

”With Nils Grevillius and his orchestra.” The phrase can be used for most of Jussi Björling’s studio recordings made in Stockholm. Sometimes that orchestra is the Stockholm Philharmonic, that of the Swedish Radio (in early days called Radiotjänst – “the Radio Service” public broadcaster which was the only one allowed in Jussi’s time) or Kungliga Hovkapellet: the orchestra of the Royal Opera, Stockholm. Most recordings with a “named” orchestra derive from concerts, broadcasts, or staged opera performances, while “his orchestra” typically met to record for Jussi’s many 78 rpm discs. From Jussi’s very first published record for His Master’s Voice of 18 December 1929 to the final recorded concert from Gothenburg 5 August 1960 Grevillius almost had a monopoly, at least for arias and other more serious songs thar required an orchestra. So who was he, and how did it come about? And who were the orchestras he recorded with?

Nils Grevillius

Nils Grevillius’s family lived in the district of Stockholm called Kungsholmen when he was born on 7 March 1893. His father edited a magazine for farmers and there was no particular musical background in the family, but they were avid visitors to the Opera. From the inauguration of its present building in 1898, the Grevillius family is said to have spent most Sundays in the top balcony of the Stockholm Royal Opera, and the same year five-year-old Nils received his first violin. He knew early that he wanted to become a violinist, and his taste encompassed all kinds of music. After he died on 15 August 1970 Svenska Dagbladet’s Gunnar Unger wrote about how Nils Grevillius played dance music at a student ball in Uppsala the evening before his final exam concert at the Academy for Music in Stockholm. The ball finished at six in the morning, when Nils took the seven o’clock train to Stockholm, rested for a couple of hours and then played one of the Wieniawski concertos well enough to win the Marteau prize: a better instrument. He was eighteen.

Light music by” Nils Grevillius and his orchestra”: two record sides ”Södermälarstrands-rapsodi”. Söder mälarstrand is the quay in Stockholm south of the Lake Mälar. The arranger Kyndel probably was Nils Kyndel, and the recording is said to have been made on Januar 14, 1932:

Södermälarstrands-rhapsody, part 1

Södermälarstrands-rhapsody, part 2

That same autumn the young lad started in the first-violin section of the Royal Orchestra. In the small hours he played dance music to earn money in order to study conducting abroad. He wanted to go to Sondershausen, and in 1913 he had achieved his goal. Home again the following year he was employed as assistant conductor of the newly formed Konsertföreningens orkester – the orchestra of the Stockholm Concert Association which much later would evolve into the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic. His debut there took place 1 March 1914. The orchestra played in the Auditorium at Norra Bantorget, and until spring 1920 he conducted 140 concerts of a broad, often popular repertoire. The orchestra’s first conductor, the Finn Georg Schnéevoigt led the more serious works. From 1918 Grevillius also conducted at the Opera, mostly ballets and more popular operas, about the same number of nights.

Between the summers of 1920 and 1922 Grevillius was again abroad, although half-a-dozen concerts with the Stockholm Concert Association during those two seasons prove that he sometimes came home. He was one of the staff conductors for the Ballets suédois based in Paris, and the website of the Vienna Symphony Orchestra lists eight concerts by Grevillius in early 1922 and again in March 1923. Now some of his repertoire is more adventurous: two evenings of Mahler and Beethoven’s Ninth symphony. These concerts were held in the “golden hall” of the Musikverein. His debut there had been with the Vienna Philharmonic already on 13 November 1921. This was a charity concert for retired members of the orchestra where a Berwald overture, Hugo Alfvéns fourth symphony and some smaller pieces were followed by Tchaikovsky’s 1812. On the 25 December there was another concert with the Vienna Philharmonic in the Musikverein. The intention was that Alfvén himself would conduct the symphony at a gala concert in aid of the Swedish Society in Vienna, but Grevillius stood in for him. In addition to the symphony Ravel and Wagner were on the programme.

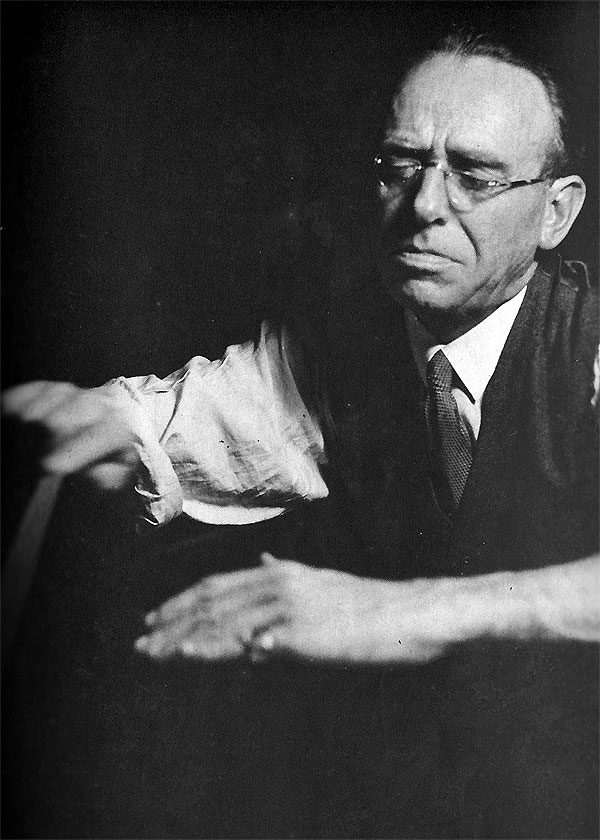

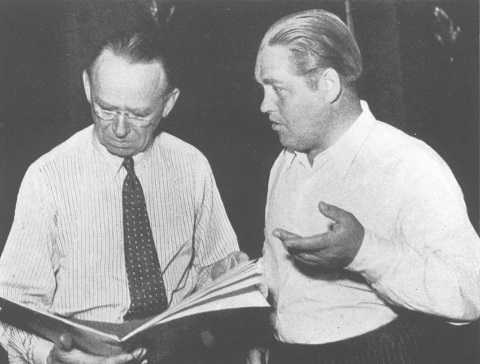

Nils Grevillius and Jussi 1944

of the Royal Orchestra, remaining in that position until he retired from the Opera at age 60 in 1953.

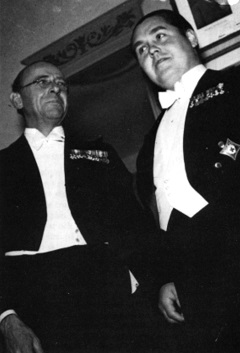

Nils Grevillius, Brita Hertzberg, Max Hansen and Einar Beyron

In parallel, the new radio medium became an important arena for Nils Grevillius. Radiotjänst started its operations on 1 January 1925, with music an important component already from the start. After a couple of years there was a “Radio Orchestra” consisting of musicians from the Concert Association (about 20), the Opera (8, mostly wind players) and some free-lancers, among them the composer Hilding Rosenberg on various keyboard instruments. For the musicians from the city’s two orchestras this was a second job. A permanent conductor was needed, and 1927–39 he was Nils Grevillius. In the 1930s the orchestra expanded to more than thirty members and broadcast concerts with Grevillius mostly five times per month. At the same time he was the chief conductor of the Stockholm Opera.

In 1937 there was a reorganization. The Concert Association Orchestra achieved year-round employment for the first time – their previous contracts had been for just seven months, necessitating extra work. It now had a second identity broadcasting as Radiotjänsts symfoniorkester – the symphony orchestra of the Radio Service. For the first two years Nils Grevillius remained chief conductor of what now had been formalized as regular broadcasts by the future Stockholm Philharmonic.

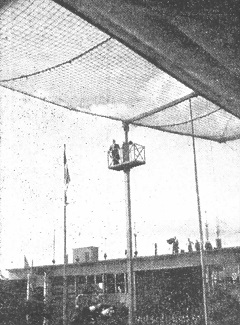

Nils Grevillius at the top of the elevator during the filming of the movie Forward to Success

broadcasts without live auditors. Adding rehearsals, gramophone recordings and smaller broadcasts the total probably is several programmes per week for two or three decades. The pace is reduced when he approaches 60. On the one hand one reads about his immense knowledge of repertoire and a routine which made him highly useful. On the other hand there are claims that his “Bohemian lifestyle” (but he did have a wife and two daughters) made him less suited for his role as head of the Royal Orchestra.

It was said that his favourite composer was Puccini. At the Opera he led almost 600 performances of his operas – that is almost one in four of the evenings he spent there – with Bohème as a particular favourite (roughly 200 times). Operas by Mozart and Beethoven are totally missing, while Gounod’s Faust and Roméo et Juliette together number 145 performances. Wagner turns up mainly in Grevillius’s later years for a total of 113 performances, but never Tristan und Isolde or Parsifal. The Stockholm Opera had conductors which were considered more suitable for those.

One notes how happy Grevillius must have been to conduct operetta, in his days an annual feature of the Royal Opera’s playbill. Radiotjänst with its single national programme also mounted operettas which often were conducted by Grevillius, and when he had retired from the Opera he was in charge of four productions 1954–57 at the Oscar’s Theatre: The Merry Widow, Die Csárdásfürstin, Can-can, and La belle Hélène. “No living Swedish conductor has more attractive movements or a more elegant use of his arms” Teddy Nyblom wrote in a history of that theatre. And after Grevillius had died similar qualities were stressed: “Grevillius had the sensuous fire and the generous feeling for how singers need to expose all their possible vocal splendour, but there was also the strict rhythmic precision. Grevillius’s conducting had a high degree of technical elegance, but at the same time he impressed as one of the most immediate and maybe even uncomplicated musicians our country has known. He worked from inspiration and provided inspiration.” (Leif Aare, Dagens Nyheter.)

Part of a potpourri from The Merry Widow that Grevillius recorded May 14, 1930. The anonymous soprano is said to be Helga Görlin, who often sang with Jussi Björling at the Stockholm Opera.

Potpourri from The Merry Widow

That Nils Grevillius “and his orchestra” were given the task to make gramophone recordings with Jussi Björling and other Swedish singers with the new microphone technology in the late 1920s was a natural choice. He knew all the musicians of the Stockholm Concert Association and the Royal Orchestra, and those who also worked for the radio could form the nucleus for the rather small ensembles needed. He did not object to lighter repertoire and was willing to assist singers to “expose all their possible vocal splendour”, as Aare described it. “A music that lived, breathed, throbbed and burnt, that sang, rejoiced and wept” – this is how Gunnar Unger in Svenska Dagbladet described what Grevillius had to offer following his death in 1970. When he sometimes was criticized it was for his turgid tempi in the languorous love duet in Madama Butterfly or insufficient philosophical depth in Der Ring des Nibelungen – both maybe qualities that many in his audience were happy with.

Until December 1936 Jussi Björling’s recordings (all for His Master’s Voice) were meant for the Swedish market. The repertoire was mixed, and the operatic arias he recorded were in Swedish translations. Most recordings were done in the Stockholm Concert Hall, either its small auditorium or in the even smaller “Attic” hall (now renamed after Grünewald and Aulin, respectively). For more popular songs the orchestra was just 12–15 musicians and could be accommodated in the Attic hall. From that month on most of his records were released internationally and standards were raised. When recordings of arias for an international audience started the orchestra grew to over 40 (8 first violins etc.).

Click on the image to enlarge it

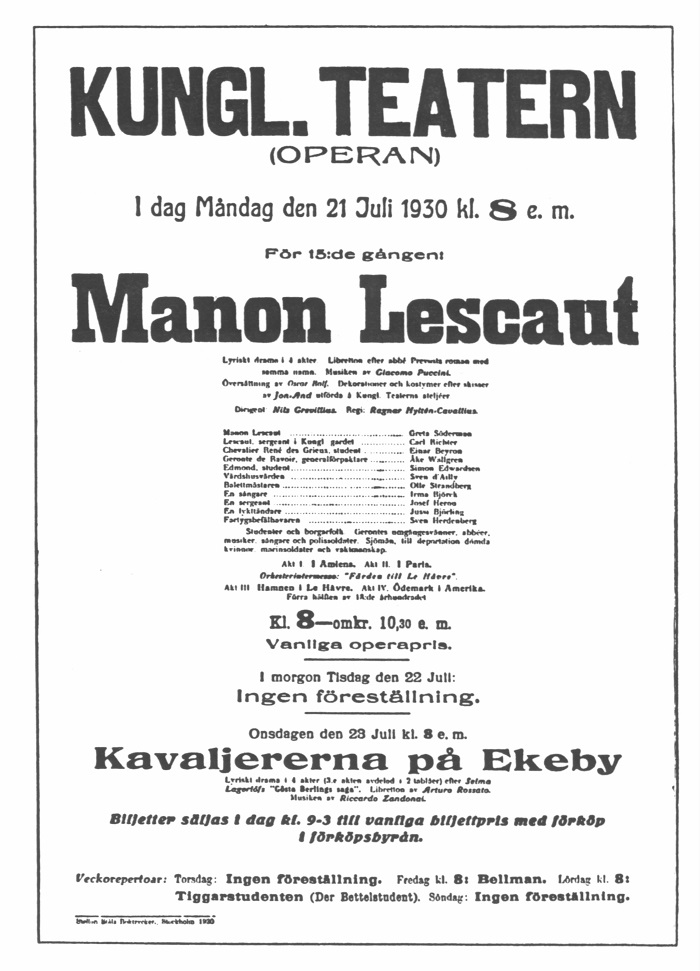

discs with Joseph Hislop and Greta Söderman. This production had had its first night on 22 November 1929 conducted by Grevillius, and Jussi Björling would make his first appearance on the Opera’s stage in the brief part of the lamplighter in July 1930.

A little more than one year earlier, during autumn 1928, both HMV and Odeon recorded excerpts from another Italian opera which was new to Sweden: Riccardo Zandonai’s I cavalieri di Ekebù. Almost an hour of music was documented conducted by Grevillius and reissued on LP in 1974. Also in that opera Jussi would have a small part when it remained in the Opera’s repertoire until 1936, almost always with Grevillius conducting.

The majority of Jussi Björling’s many performances at the Stockholm Opera were led by other conductors than Nils Grevillius. In addition to I cavalieri di Ekebù and Manon Lescaut there were a few others like Louise which were typical “Grevillius operas”, and where he had small roles. His first leading role under Grevillius was Roméo in Gounod’s Roméo et Juliette. Grevillius conducted almost every performance of Knyaz Igor, an opera which Jussi sang as many as 35 times, and when he started singing Cavaradossi in Tosca in the autumn of 1933 it was self-evident that the royal court conductor would lead this opera by his favourite composer. I’ll not enumerate some forgotten operas conducted by Grevillius where Jussi had minor parts. But Grevillius also conducted the world premiere of Atterberg’s Fanal, and the aria they recorded together a little more than a year later is a rare example of Jussi in a contemporary work. Among collectors it is called a creator’s record when the original cast members take part.

Click here and listen to Jussi as Martin Skarp from opera Fanal, recorded 4 March 1934, from Naxos's album 8.110722S. "I männer över lag och rätt”.

Now that Jussi had become the theatre’s leading tenor the list of collaborations with Grevillius is augmented with Faust, Bohème, Il tabarro, Fanciulla del West, Die Fledermaus and a few more where Jussi’s part is less important, or in which they appeared together just a few times. In the 1950s when he added Des Grieux in Puccini’s Manon Lescaut to his repertoire Grevillius conducted four out of the six times Jussi sang this role in Stockholm. But it is likely that Herbert Sandberg and possibly also Kurt Bendix conducted more performances with Jussi Björling at the Stockholm Opera than Nils Grevillius did. His position as the conductor who collaborated with Jussi the greatest number of times is due to gramophone recordings and concert work.

August 1949 saw the final recordings with Jussi Björling and Nils Grevillius which were made in the small auditorium of the Stockholm Concert Hall, with musicians from its orchestra, and issued by HMV on 78s. An almost twenty year long period was at its end which had given us about 100 record sides. The next year they met again for a few numbers commissioned by US RCA Victor that were published only on the new 45 and 33 rpm discs. 1957 and 1959 there were more recordings for RCA of arias and songs by Björling and Grevillius: one 10-inch and one 12-inch LP, and some songs which at first only came out on 45s.

Recording in the concert hall in August 1959

Ditto

Shortly after Jussi’s sudden death in 1960 their final concert together in Gothenburg 5 August 1960 was also issued on LP.

Their 30-year collaboration is also documented by other live material which has been published repeatedly. Only Roméo et Juliette 1940 and Manon Lescaut 1959 exist as complete performances from the Stockholm Opera, both with Hjördis Schymberg, but parts of Bohème and Faust have been issued, and concert renditions of arias and songs from his many broadcasts.

When Jussi died Nils Grevillius was 67. The intention had been to record a TV programme of duets during the autumn, where Jussi Björling would sing together with Margareta Hallin. That recording took place with Nicolai Gedda replacing Jussi, and some numbers from it are included on two Bluebell CDs celebrating Gedda and Hallin, respectively. In May 1965 Gedda recorded an LP of Swedish “Jussi repertoire” for Swedish RCA. In 1962–64 Grevillius had also recorded three LPs with the Stockholm Philharmonic, including Alfvén’s third and fourth symphonies. In the spring of 1964 ha performed for the last time at the Stockholm Concert Hall and also at the Royal Opera, in the latter case with his beloved Puccini: Madama Butterfly which he had conducted there for the first time in 1918, four times with Jussi Björling. For some of the 1964 performances Pinkerton was Jussi’s son Rolf. Even later there were some opera concerts with the Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra, the final one in June 1966.

Nils-Göran Olve

Click here for Jussi of the Month Summary